article_detail

A history of Aledo

The location of Aledo caused its rise and fall as a town of importance

The location of Aledo caused its rise and fall as a town of importance

The history of Aledo is dictated by its geographical location, which at various points in its history has become both the reason for its expansion and the cause of its decline.

The town enjoys an important strategical advantage, being high in the Sierra Espuña on a rocky outcrop which made its fortifications impregnable. However, this also rendered crop production difficult, and its status as a border town lead to a great deal of insecurity in its checkered history. It is dominated by impressive military fortifications, drawing in visitors who are attracted by its old world charm and proximity to the natural beauties of the Sierra Espuña, although the economy today is based mainly on agriculture.

Prehistory of Aledo

The area surrounding Aledo was certainly inhabited in pre-history, the most important site discovered being that at Cabezo de las Cuevas. This is a natural, rocky shelter which was first inhabited during the Upper Paleolithic, within the third and last period of the Stone Age, broadly speaking between 40,000 and 10,000 years ago.

Few details are known about the subsequent pre-history in this area as the sites investigated have not revealed a great amount of information, although it is believed that there was subsequent settlement between the Stone Age and the next sites of note which date from the Argaric Culture (1800-1300 BC).

The sites of Los Allozos II and Cabeza de la Rambla de Molinos relate to the Argaric culture and are typical of the locations chosen by these people: They chose places with strategic advantages, usually high up on a hill and with water supplies readily available, giving them natural defences against attack and a perfect viewpoint from which to watch over the movements of people, flocks, herds and merchandise. The Argarics were a technologically advanced culture who produced impressive artefacts in both metals and ceramics, and inhabited various sites within the Region of Murcia.

Aledo under the Romans

This area of southern Spain was occupied by the Romans in 209BC, when they invaded vía what is now Cartagena and built a city from which they were able to control the area, both on the coast and inland. From the port they shipped out raw materials harvested from across the region, including marble from the north-west, silver and lead from the Sierra Minera of La Unión and Cartagena, esparto grass, salted fish sauces manufactured along the coast and olive oil and wheat grown inland.

This area of southern Spain was occupied by the Romans in 209BC, when they invaded vía what is now Cartagena and built a city from which they were able to control the area, both on the coast and inland. From the port they shipped out raw materials harvested from across the region, including marble from the north-west, silver and lead from the Sierra Minera of La Unión and Cartagena, esparto grass, salted fish sauces manufactured along the coast and olive oil and wheat grown inland.

Agricultural villas were built throughout the region, producing wine, olive oil and wheat, and the most important Roman remains in Aledo fall into this category. Aledo has Roman agricultural villa remains at Los Allozos, Huerta Nueva and Juncarejo, as well as the remains of civil engineering projects such as a water deposit built at Venta Meras and a burial ground at El Caño.

There is little to be seen today and it is also very difficult to actually locate these remains.

Following the same defensive principles as the Argarics before them, the Romans also selected sites on high ground, giving good vantage points to watch over communications routes.

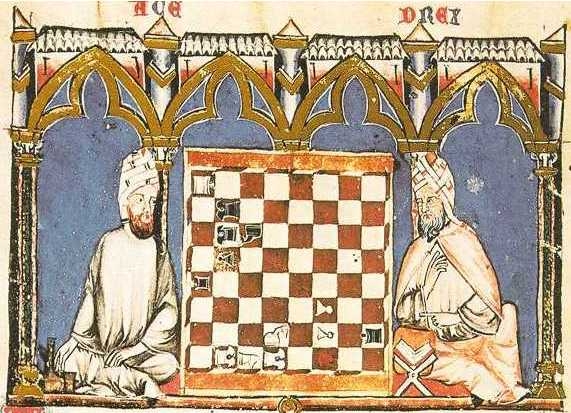

The Moorish occupation

By the 4th century AD the Romans had lost their grip on Europe and for several hundred years there was instability as Goths, Visigoths and Vandals occupied southern Spain. By the early 8th century the area was ruled by the Visigoths but the Moors, led by Abd al Aziz, saw a weakness and invaded from Cádiz.

By the 4th century AD the Romans had lost their grip on Europe and for several hundred years there was instability as Goths, Visigoths and Vandals occupied southern Spain. By the early 8th century the area was ruled by the Visigoths but the Moors, led by Abd al Aziz, saw a weakness and invaded from Cádiz.

In 713 the Pact of Tudmir was signed, giving control of south-eastern Spain to the invaders although the Visigoth overlord Theudimer (Tudmir in Arabic) was nominally in charge as a wali (governor). His son retained the position, but following his death the area became a dependency of the Emir of Córdoba.

In 825, work commenced to build the Moorish city of Mur-siya, now Murcia, within the area known as Tudmir. According to the Arab geographer Al-Idrisi this also included Orihuela, Cartagena, Mula, Lorca and Chinchilla, with Lorca as the main administrative centre.

The first documentary mention we have of Aledo comes from 896 AD, when it was a “hisn” or fortification, and in that year the Emir of Córdoba sent troops to the kingdom of Tudmir to quash a rebellion led by Daysam ben Ishaq.

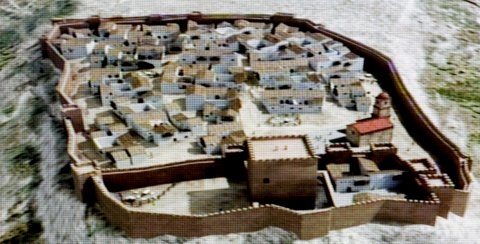

Aledo looks out over a large swathe of land between Andalucía and the Levante coast, making it the ideal location for a fortified defensive structure. As the Moors consolidated their position, they built substantial fortresses from which they could control their territory, and in the 11th century the first primitive fortifications were demolished to build a more substantial and important structure.

Aledo looks out over a large swathe of land between Andalucía and the Levante coast, making it the ideal location for a fortified defensive structure. As the Moors consolidated their position, they built substantial fortresses from which they could control their territory, and in the 11th century the first primitive fortifications were demolished to build a more substantial and important structure.

However, by the end of the 11th century the Reconquista was under way as the Catholic powers of Castilla and Aragón started to move southwards in a bid to claim the territories ruled by the Moors. As the two rival kingdoms moved across Spain the south-western flank was headed by Alfonso VI of Castilla, who took Toledo in 1085, and the following year Aledo was captured by the famed Castilian knight, García Jiménez, who used it as a strategic base for the forces who carried out raids in Murcia, Almería, Granada and Jaén.

Aledo became the main base for all Christian troops in the south-east of Spain, and the main stronghold of the Reconquista forces of Alfonso VI.

In this same year the Taifa rulers of Al-Andalus, who controlled the Taifas of Seville, Badajoz, Granada, Almería and Málaga in southern Spain, asked the Berber Almoravid dynasty from Morocco for their assistance in fighting off the advancing armies of the Christian Reconquista.

On 23rd October 1086 the battle of Sagrajas, also known as the battle of Zalaca or Zallaqa took place: the name comes from the word "al-zallaqah", meaning slippery ground, due to the amount of blood shed on that day.

The Castilians were defeated but the Almoravids, led by Yusuf ibn Tashfin, and their allies suffered heavy losses, preventing them from immediately banishing the Christians from the territories they had gained. In subsequent years the conflict continued and in 1090 Yusuf ibn Tashfin crossed the Mediterranean again to annexe the lands owned by the Tarifa princes he had assisted four years earlier. This was at the request of the inhabitants, who were fed up with their weak rule and religious indifference.

Aledo was one of their main targets, referred to by Ibn Al Abbar as “The Great Impregnable”.

Aledo was one of their main targets, referred to by Ibn Al Abbar as “The Great Impregnable”.

There were two main reasons for this invasion: firstly, the desire to expel the Castilians from the territory of Islam, and secondly as a corrective measure against Ibn Rasiq, the Moorish king of Murcia who was declaring independence.

In around 1092, the Almoravid monarch Yusuf ibn Tashfin, supported by Tarifa troops from Seville, Almería, Granada and Murcia, laid siege to the town with towers, ditches, palisades and siege engines. However, the strength of the defences was so great that the stand made by the inhabitants was threatened only by hunger and the onset of winter. They held out until Alfonso VI himself arrived with his army, but when he entered the fortress the King found that the walls had been mostly destroyed and the garrison reduced to just a couple of hundred men.

He had two choices: rebuild at great expense or abandon the garrison. He chose the latter and ordered that the fortress be torn down and burnt, leaving Aledo to return to the control of the Moors, and it was subsequently rebuilt by the Moorish forces.

Aledo, The Reconquista and the Order of Santiago

By 1243 the tables had turned, and the Castilian forces had gained enough strength to push the Moorish forces to a point of virtual surrender in much of southern Spain. In 1243 ambassadors of the Moorish king of Murcia, Muhamad Ibn Hud, signed the Treaty of Alcaraz with Prince Alfonso of Castile, effectively handing over the kingdom of Murcia to Castile. The rights of the Moorish population would be respected - in theory, at least - but taxes would be paid to Castile. Although much of the population accepted the transition, the fortresses of Lorca, Mula, Aledo and Cartagena refused the terms of the surrender and had to be subdued by force. Aledo fell to the Christians in 1244.

By 1243 the tables had turned, and the Castilian forces had gained enough strength to push the Moorish forces to a point of virtual surrender in much of southern Spain. In 1243 ambassadors of the Moorish king of Murcia, Muhamad Ibn Hud, signed the Treaty of Alcaraz with Prince Alfonso of Castile, effectively handing over the kingdom of Murcia to Castile. The rights of the Moorish population would be respected - in theory, at least - but taxes would be paid to Castile. Although much of the population accepted the transition, the fortresses of Lorca, Mula, Aledo and Cartagena refused the terms of the surrender and had to be subdued by force. Aledo fell to the Christians in 1244.

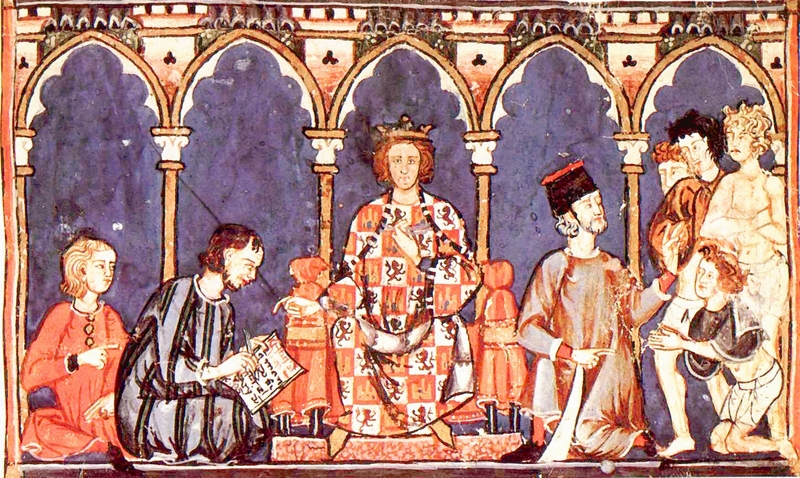

On 14th April 1257 Alfonso X “El Sabio” awarded Aledo to the Order of Santiago, whose Master at the time was Pelay Pérez Correa, and the town was to be closely linked to the Order for more than 500 years. The task of the Order’s knights was to protect and repopulate the town, and the town council included members of the Order as well as two “alcaldes”. There was also a parish priest.

Despite their efforts, by 1271 no new Christian population had reached Aledo and the population which remained were all moorish farmers, many of whose families had been in the area for centuries .

The Moorish quarters paid the Order of Santiago 487 “maravedís” per year in three instalments (February, June and October), and to attract Christians, Juan Osórez, the Master of the Order, gave Aledo the status of “New Town” in 1293. This implied the concession of franchises and certain freedoms to any Christian arrivals.

In 1350, Master Fadrique (the son of Alfonso XI) gave the local administrator Bernal Alonso the duty of distributing the land around the town to both locals and people from outside, on condition that they settled in Aledo and cultivated at least three “tahullas” (about 3,400 square metres) of grapes for the first three years of their tenure.

Aledo continued to be inhabited by Moors until the 14th century, although these were “Mudéjars”, who paid the Christian administrators for the right to stay in Christian territory. This continued presence of the Moors rather than new Christian settlers was due to the geographical location of the town, high up, out of the way, difficult to reach, and close to the frontier with the kingdom of Granada, which had remained under Moorish control. This meant that the area was insecure and unsafe, and there were frequent raids into the territory of Murcia.

During the century the town generated an annual income of 125,000 maravedís, and in the case of war was obliged to contribute five fully armed warriors.

As the town began to grow there were often disputes regarding the boundaries of the township with Lorca, Alhama and Mula, especially the latter: Aledo owned the village of Pliego, where there was another Mudéjar town, with a castle where the inhabitants took refuge when threatened by attackers.

For two and a half centuries Aledo continued to be an important strategic fortress on the border between the kingdom of Murcia and the Islamic world, and the best remembered event is the Battle of Los Alporchones, which was fought on 17th March 1452.

In the course of the battle, troops from Lorca and Murcia defeated the raiding forces from the Nazarí kingdom of Granada and Alfonso de Lisón, the commander of Aledo, killed the “alcalde” of Baza and took his counterpart from Almería prisoner, although he later died from his wounds. So grateful were the administrators in Lorca for Alfonso’s contribution that they rewarded the town of Aledo with some of Lorca’s land.

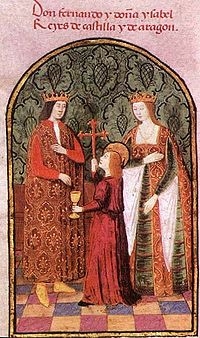

Wars between Castile and Granada continued, and in 1474 the two most powerful Christian kingdoms became united under the rule of Isabel of Castile and Fernando of Aragón, the marriage of the two monarchs effectively uniting Spain for the first time. The couple are now known as the Catholic Monarchs.

Wars between Castile and Granada continued, and in 1474 the two most powerful Christian kingdoms became united under the rule of Isabel of Castile and Fernando of Aragón, the marriage of the two monarchs effectively uniting Spain for the first time. The couple are now known as the Catholic Monarchs.

In 1489, the Catholic Monarchs were accompanied by a military party from Aledo, including 20 horses, in their attack on the kingdom of Granada. When Granada fell to the Catholics in 1492, Aledo was suddenly no longer a frontier outpost, and although this made the area safer for civilian inhabitants, it led to the town’s gradual decline as the neighbouring town of Totana became more populous.

The Catholic Monarchs were also the administrators of the Order of Santiago, and in 1494 they confirmed the privileges of Aledo, declaring the inhabitants exempt from taxation. However, from the end of the century onwards, as the population moved to the now secure fertile plains of the Guadalentín valley below, the once prestigious and vital fortifications became almost an irrelevance.

Aledo and the Revolt of the Comuneros

Following the death of both monarchs there was a period of instability, which culminated in an event called the Revolt of the Comuneros. This was lead by Pedro Fajardo, the first Marqués de los Vélez, a protest against the policies of the ruling classes and the absence of King Carlos V from Spain. Carlos was the Holy Roman Emperor and ruled vast tracts of Europe and the Americas, so was unable to eliminate the corruption which ensued in the absence of the monarch.

Following the death of both monarchs there was a period of instability, which culminated in an event called the Revolt of the Comuneros. This was lead by Pedro Fajardo, the first Marqués de los Vélez, a protest against the policies of the ruling classes and the absence of King Carlos V from Spain. Carlos was the Holy Roman Emperor and ruled vast tracts of Europe and the Americas, so was unable to eliminate the corruption which ensued in the absence of the monarch.

In 1520, under threat from the Revolt, the ruling classes of Totana sought refuge in the castle of Aledo. The townspeople attempted to take the fortress by storm and it was surrounded by a horde of 5,000 men for eighty days. During this short period Aledo relived its famed strength as an unassailable fortress, and the captain in charge of the castle not only managed to withstand the siege, but even designed a cunning night manouevre which ended in the Comuneros being driven out to Murcia. In recognition of this heroic defence, Emperor Carlos V awarded Aledo the status of “Leal” in 1521.

Aledo loses prestige to Totana

During the 16th century the population of Aledo decreased while that of Totana grew. At the start of the century the town in the valley already had more inhabitants than the mountain town, and in an attempt to halt the trend the Council of Aledo ruled that no more houses could be built in Totana except those which were needed for the farm workers. They also ruled that all those natives of Aledo living in Totana should return or face a fine of 2,000 maravedís.

However, this order was disobeyed and even the councillors, the local oligarchy and the parish priest eventually moved to Totana in the course of the next few years. As of 1520 the sessions of the council were held in Totana, and soon the town was renamed as “Villa de Aledo y Totana”.

During the events of the Revolt of the Comuneros the castle had been severely damaged. This was one more reason for Totana to become the head of the municipality, added to the desire of the wealthiest families to exploit and control the rich farmlands in the valley. For these reasons the situation which had existed since the 13th century was turned on its head, with Aledo becoming dependent on Totana: in 1550 it was agreed that council meetings should be held in Totana permanently, and Aledo was recognized as a borough within Totana. Three years later Pope Julius III approved the transfer of the Order of Santiago from Aledo to Totana.

Aledo and the War of Succession

Unlike other towns under the control of the Order of Santiago, such as Ricote, by the 16th century Aledo had no Moorish inhabitants except in the town of Pliego. When the Moors rebelled in the Alpujarra mountains of Granada in 1568, Captain Juan Mora led a hundred men from Aledo who joined the forces of Lorca to fight in the Sierra de Guadaque, Berja and Almanzora. After the war, 86 Moors were established in Totana and Aledo until they were deported from Cartagena in 1610, following an order made by the King Felipe III to expel all Moors and their successors from Spain.

The deportations particularly afffected areas such as Murcia, where a large part of the agricultural labouring work and farming was carried out by these families, the result being food shortages and rising prices in the cities. 300,000 people were deported, an excuse for the bankrupt Crown to seize all of their lands and possessions.

By the Law of Seven Leagues, Aledo was under obligation to provide military support for other towns and cities such as Mazarrón and Cartagena in the case of raids by Berber pirates. In the 17th century two companies existed to meet this obligation, one cavalry and the other infantry.

At the start of the 18th century, in the War of Succession, Aledo joined the rest of the kingdom of Murcia in supporting the cause of the House of Borbón, and contributed both money and men to the campaign of Luís Belluga, the Bishop of Cartagena and commander of the forces of Murcia and Valencia. In recognition of the support given, Felipe V confirmed the historic privileges of Aledo and Totana, adding the title of “Noble” to the legend on the coat of arms of the two towns.

The 18th century: Aledo and Totana part company

The most important religious building in Aledo is the church dedicated to Santa María la Real, next to the fortress in the old centre of the town. The original was founded in 1471 by the Masters of the Order of Santiago, and was consecrated in the name of Nuestra Señora de la Asunción in 1741.

The most important religious building in Aledo is the church dedicated to Santa María la Real, next to the fortress in the old centre of the town. The original was founded in 1471 by the Masters of the Order of Santiago, and was consecrated in the name of Nuestra Señora de la Asunción in 1741.

On 15th July 1761, due to the dilapidated state of the building, the order was given for a new church to be built, and it was finished in 1804, thanks in no small part to the contribution of Carlos Luís de Borbón, pretender to the Spanish throne.

The architecture is baroque with a stone façade flanked by two matching towers. At the foot of the church is the Capilla del Bautismo, a peerless work of construction in terms of the acoustics inside.

The differences between the towns of Aledo and Totana became more accentuated as the century wore on and by the middle of the century the census showed that only 201 people lived in Aledo as opposed to 2,303 in Totana. The main sources of income for the municipality were wheat, barley, oil, wine and fodder, and there was also corn, hemp and salsola. Farmland was owned by local smallholders, and farm labour was performed by about 500 people who received a wage of 4 reales per day.

The process of segregation was initiated by Aledo in 1784, and in 1793 it became a separate municipality, with its own jurisdiction, marking the end of centuries of union although the boundaries were not finalized until 1795. Despite the official separation, responsibility for some common interests was still shared, including water and some taxation issues.

Aledo and the War of Independence

In 1808 a series of tumultuous events were set in motion in Spain. The abdications of the Spanish kings led to Napoleon Bonaparte’s brother José occupying the throne, and a period of repression by the French led to the War of Independence, or Peninsular War. The inhabitants of Aledo and their local leaders were indignant in their rejection of French rule.

In 1808 a series of tumultuous events were set in motion in Spain. The abdications of the Spanish kings led to Napoleon Bonaparte’s brother José occupying the throne, and a period of repression by the French led to the War of Independence, or Peninsular War. The inhabitants of Aledo and their local leaders were indignant in their rejection of French rule.

On 26th May 1808 a religious and civil procession was followed by a public protest and affirmation of support for the deposed monarch Fernando VII ("El Deseado"). There were cries of “Viva Fernando!” and “Muera Napoleón!” (“Death to Napoleon!”), and the whole of the town was in uproar.

Acting on instructions from the government in Murcia, which was led by the Conde de Floridablanca, the town took up arms and prepared to resist the approaching French troops.

Napoleon’s forces made sporadic appearances and the cost of living soared due to the population neglecting their crops in favour of armed struggle and the large number of people seeking shelter in the mountain town. The price of a bushel of wheat rose to 480 reales, and the population suffered from hunger, poverty and an outbreak of yellow fever in 1810, which caused many deaths in the region of Murcia.

The 19th century: poverty and emigration

The return of Fernando VII to the throne in 1814 meant the reversal of the reforms implemented by the Cortes de Cádiz, and as a result Aledo was in the same situation as before the war: under the control of the Order of Santiago.The only difference was that now the inhabitants were poorer and fewer in number. Buildings, villages and even fields were in a state of ruin, and the situation was so bad that the Order of Santiago forfeited the backdated taxes they were owed by the locals.

The first half of the century saw a steady flow of emigrants to the mining regions of Almagrera (Almería) and Cartagena. After 1840 many of the people of Aledo also went to Catalunya and even crossed the Atlantic to Argentina, Uruguay, Brazil and, above all, Cuba.

The result was a drop in the population, which fell to 1,541 in 1860 to 1,471 in 1887, and Aledo became a poor, isolated town, consisting of about three hundred humble dwellings. The only source of income was esparto grass, which was harvested and taken by mule to Cartagena and Mazarrón, from where it was exported.

Even the freeing from encumbrance of ecclesiastical properties did little to halt the slide, with 65 per cent of the land made available in the municipality by this legislation being acquired by just two families from Totana (the Coutinhos and the Garrigues) and one from Lorca (the Alcaraz family).

In general terms throughout Spain, the last thirty years of the 19th century, after the Restoration, were a period of expansion, but this was not the case in Aledo. The main reason was the lack of infrastructures in and around the town, and the strained relationship it maintained with its neighbour, Totana: the larger town in the valley controlled the water in the area, and even took 60 square kilometers of land from Aledo. Lacking resources to oppose the neighbour’s supremacy by means of legal action, Aledo was powerless to avoid its own decline.

The population continued to fluctuate between 1,000 and 1,500, and local politics was dominated by Mariano Vergara, a lawyer, philanthropist and man of letters, who was named Marqués de Aledo in 1887.

The population continued to fluctuate between 1,000 and 1,500, and local politics was dominated by Mariano Vergara, a lawyer, philanthropist and man of letters, who was named Marqués de Aledo in 1887.

The 20th century: emigration to France

The trend of emigration continued into the 20th century, despite a brief boom in the sales of esparto grass after the Civil War ended in 1939. Unfortunately the esparto industry went into crisis in the 1950s, before Aledo had had time to modernize its economy, and by the following decade 85 per cent of the local population found themselves obliged to look for a way of making a living elsewhere. Many emigrated to the south of France seeking agricultural work.

The number of habitants fell from 1,368 in 1950 to 1,057 in 1970. However, when those who had travelled to France returned home and invested the money they had saved, some new life was breathed into the town.

Almost all the inhabitants were now able to own land to some degree, and the last thirty years of the 20th century saw the modernization of agriculture. Table grapes and almonds replaced traditional crops, cooperatives were formed and the arrival of piped water enabled the installation of irrigation systems.

Even so, by the end of the century the situation in Aledo hadn’t improved much. The population remained stagnant and the economy was undeveloped, with the geographical location, so ideal for its bygone military prominence, now proving a handicap due to the scarce natural resources of the area.

Aledo in the 21st century

The new millennium has not brought about any abrupt change in the fortunes of Aledo. The population was still only 1,022 in 2018, spread very thinly over the municipality at a density of only 20 inhabitants per square kilometre, and the town is still clustered around the old medieval fortress.

The new millennium has not brought about any abrupt change in the fortunes of Aledo. The population was still only 1,022 in 2018, spread very thinly over the municipality at a density of only 20 inhabitants per square kilometre, and the town is still clustered around the old medieval fortress.

81.3% of the available land is used for agriculture, with only 400 of the 4,100 hectares irrigated. 74% of those working are employed in the agricultural sector, and 17.3% in service industries.

However, the castle may still prove important in the history of Aledo, with rural tourism becoming increasingly popular. Visitors are drawn to the town by its unique location and its narrow medieval streets, as well as the surrounding countryside and proximity to the forested areas of the Sierra Espuña regional park. Annual celebrations such as the Fiestas in August and the Auto de los Reyes Magos in January also draw in many visitors to the town.

Aledo is one of the best conserved historical towns in the Region of Murcia, and great care is taken to ensure that new buildings conform to the style which has dominated its streets for hundreds of years. Just a step away from the Sierra Espuña, it is now attracting more and more visitors every year, and there is even a small but growing population of residential tourists from countries in the north of Europe who have chosen to live in the municipality.

Address

Plaza del Castillo, s/n 30859 ALEDOTel: 968 484 422

Mobile: 696 962 116

Mobile: 696 962 116

Loading

Oficina de Turismo de Aledo

The tourist information office of Aledo is located within the Torre del Homenaje, the keep of the castle at the top of the old town, and although it is possible to drive to within just a few metres of the tower and park in the streets just below, this can be an unnerving experience for those unaccustomed to driving in narrow streets. It may be advisable to park lower down in the town close to the Town Hall (Ayuntamiento) and walk 5 minutes up to the castle.

Aledo is a hilltop town, originally built by the Moors and then rebuilt by the Christian forces of the Reconquista, who took this area during the 13th century and converted it into a Christian stronghold from which to continue their fight to claim all of Spain for a further 250 years.

Aledo is a hilltop town, originally built by the Moors and then rebuilt by the Christian forces of the Reconquista, who took this area during the 13th century and converted it into a Christian stronghold from which to continue their fight to claim all of Spain for a further 250 years.

The tower is well worth a visit for the views alone, although those with an interest in geology or fossils will also find the 20 million year walk back in time down into the valley below of great interest, as the rock upon which the castle is built is renowned internationally as a location of geological interest.

The tower is well worth a visit for the views alone, although those with an interest in geology or fossils will also find the 20 million year walk back in time down into the valley below of great interest, as the rock upon which the castle is built is renowned internationally as a location of geological interest.

Aledo also contains the only surviving Picota, or pillory, in the Region of Murcia, as well as a church, the Iglesia de Santa María Real, containing two sculptures by the baroque master Francisco Salzillo. It is also within the Sierra Espuña regional park and is a good stop-off point if heading up into the mountains, and the views from the church plaza and tower are spectacular.

On 6th January it is the scene of the traditional Auto de los Reyes Magos, a musical nativity play which takes place in the streets of the town with the participation of donkeys and many of the local townspeople.

On 6th January it is the scene of the traditional Auto de los Reyes Magos, a musical nativity play which takes place in the streets of the town with the participation of donkeys and many of the local townspeople.

The tourist office is open only when the tower is open, so for enquiries at other times contact the Town Hall on 968 484422 (alcaldia@aledo.es).

For more information visit the Aledo section of Murcia Today.

View Aledo, Murcia in a larger map

article_detail

Contact Spanish News Today: Editorial 966 260 896 /

Office 968 018 268