article_detail

A history of Archena, a story inextricably entwined with the thermal baths and the River Segura

The spa and the river in Archena have attracted settlers for at least the last 2,500 years

The municipality of Archena may occupy an area of only 16 square kilometres in the Ricote valley, but it is home to comfortably the largest population of any of the towns in this part of Murcia, and archaeological evidence suggests that this is due to certain advantages which previous cultures and civilizations have appreciated for many millennia.

First and foremost of these is the existence of the thermal spring which has made Archena a spa town, and which now brings thousands of visitors to the Balneario (or spa resort) every year. But there is geological evidence that the spa has been in existence for some 15,000 years, and archaeologists have discovered prehistoric settlements dating from the Bronze Age in and around the town: it is hard to believe that the spring was not used by these peoples for one purpose or another before the beginning of documented history.

Since then other cultures to have left their mark on Archena include the Iberians, the Carthaginians, the Romans and the Moors, prior to the arrival of the Christian forces of the Order of San Juan in the 13th century. All of these different civilizations have based themselves in Archena over the last 2,500 years as the spa has acted as a magnet to human activity, and this along with the fertile land around the River Segura at the southern end of the Ricote valley has ensured that the town has survived continuously in one form or another despite some desperately difficult periods in its history.

Prehistory in Archena

There are three good reasons which contribute to explaining the existence of human settlements in Archena since before the start of recorded history, and they are all related to the geography of the area.

These are not only the thermal water spring but also the River Segura, which provides water to irrigate the fertile land in the valley it has created, and the natural communications route which runs north-west from the Segura valley and the coast towards the plains of Castilla-La Mancha and the centre of the Iberian Peninsula.

The earliest signs of human activity in Archena date from the Chalcolithic, or Copper Age, which in Spain lasted from approximately 3500 to 2200 BC, and a burial site containing the remains of 23 people along with grave goods from that period has been found. There is also a Copper Age site under excavation close to the La Capellanía industrial estate just to the east of the town (on the road between Archena and the A-30 motorway).

But as the Copper Age gradually evolved into the Bronze Age, from around 2200 BC to 1500 BC the dominant civilization in south-east Spain was the Argaric Culture, which spread to include multiple sites in the Region of Murcia, Almería, Granada, Alicante and Jaén. At this time it was found that smelting tin with copper produces bronze, and this technological development coincides broadly with other populations developing along the same lines within Europe: hence the Wessex and Armorican Tumuli belonging to the Hilversum Culture of Central Netherlands, Belgium and Northern France (broadly 2000 BC to 1400 BC), the Polada in Italy (13th and 14th century BC) and the Unetice in the Czech Republic, western Poland and Southern and central Germany (2300-1600BC).

Metallurgical skills enabled Bronze Age man to build substantial settlements as they made the processes of agricultural production easier, and individuals were able to develop specialist skills, opening up the way for trade, social development and structure, territorial organization and definition, the emergence of funeral rites and the expansion of the population.

In Archena evidence of the Argaric Culture has been round in the form of ceramics at the sites of Cabezo Redondo, Cabezo del Ciervo and Cabezo del Tío Pío.

The Argarics disappeared around 1500 BC, the general theory being that their over-exploitation of natural resources, climatic change and a limited diet caused a falling birth rate and medical problems which diminished their capacity to operate as an organized society, although there are no written records to definitively pinpoint the exact cause.

The site at Cabezo del Tío Pío, the mountain which rises from the eastern bank of the Segura, opposite the Balneario, also provides evidence of an important presence of the Iberians in Archena in the 5th, 4th and 3rd centuries BC. The Iberian tribes were dominant in what is now Spain from approximately the end of the 6th century BC until the arrival of the Carthaginians and then the Romans in the 2nd and 1st centuries BC, and maintained trading relations with Greek and Phoenician traders who reached inland from the Mediterranean by travelling up the Segura.

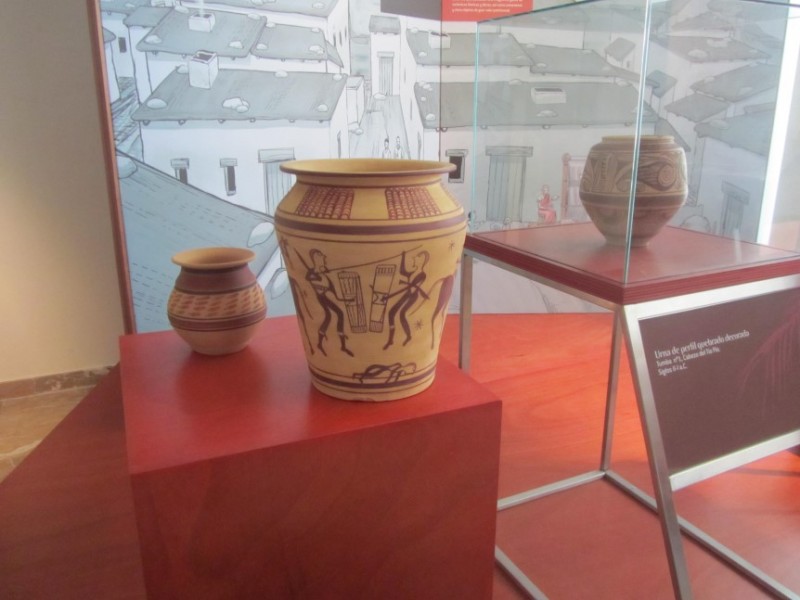

Such prolonged contact with Greek culture made a mark on the Iberian art which has been found in Archena, and this can be seen in the ceramics discovered at Cabezo del Tío Pío. The items unearthed include amphorae, plates, urns, brooches and drinking vessels, and so distinctive is the decorative style that it has been given its own name of “Elche-Archena”.

This style features figurative scenes on large containers, and one of the best known items is the “Vaso de los Guerreros” (or Warrior Vase), which is now housed in the national archaeology museum in Madrid. This is a vessel measuring 41 centimetres in height and 36 cm in diameter decorated with scenes depicting hunting and armed combat between fighters on horseback and foot warriors, interrupted by a boar-hunting tableau, and it dates from the second half of the 3rd century BC.

There is an interesting display containing replicas of these items at the town museum.

The Romans in Archena

During the third century BC the Carthaginians were briefly in control of much of what is now the Region of Murcia, and some of their garrisons are known to have been stationed in Archena, but after just 18 years they were ousted by the arrival of the Roman Empire in the south-east of Spain, and specifically in Cartagena, in 209 BC.

At this point, in Archena as in the rest of Murcia, the native Iberian culture suddenly became an irrelevance, and their towns and settlements began to disappear along with their language, religion and way of life as the Romans transformed their military victory into a more complete conquest. The town at the Tío Pío site was abandoned, possibly because the Romans preferred to live nearer the thermal baths, and archaeological evidence has come to light that they even rebuilt their baths at the site of the modern-day hotels after the original facilities were engulfed by a flash flood in the 1st century.

There was agriculture in the area administered from a central “villa”, but there is no doubt that the main attraction was the thermal baths, all the more so since the water here has therapeutic qualities as well as merely being warm. It may be that the name of Archena derives from the role of the baths in helping wounded soldiers to recover from their injuries, although most consider it more likely that it comes from the Latin compound “arsillasis”, or city of clay.

Extensive excavations have been undertaken in and around the baths, and the most important relics unearthed include the “lápida de los diunviros”, an inscription in stone which was discovered in the 18th century, and various columns and rooms belonging to the original Roman baths. There was also accommodation and a temple, and at this point the baths were at the centre of what may have been a Roman municipality in the 1st and 2nd centuries AD.

From the Romans to the Christians: the Dark Ages of Archena

The phrase “Dark Ages” usually refers to the period of void left by the collapse of the Western Roman Empire and the supposed stagnation and cultural deterioration between the 5th century and the Early Middle Ages.

In fact, in Spain it would be a mistake to label the period of Moorish occupation which began in the 8th century as such, but what is true is that in terms of recorded history there is little in the way of documentation which was left by the Muslims as a legacy from their centuries in power in almost the whole of the Iberian Peninsula.

Thus, in Archena, the development or otherwise of the town under the Visigoths and the Byzantines, and then under the Moors, is almost entirely obscured from our view by the passing of the centuries. The Moors had a system of defences to protect the spa, including a fortress, and this formed part of a chain of fortifications in the Ricote valley, but very little else has been established for certain.

In fact, the fortress was the chief item listed in Archena when it was entrusted to the Order of San Juan (see below), but when the town became involved in infighting in the kingdom of Castilla in the 15th century orders were given for it to be demolished in 1452.

It can be assumed that the Moors reached Archena as they advanced inland along the old Roman roads prior to taking control of Murcia in 713, and that they used and improved existing irrigation systems many of which had been created by the Romans. But these conclusions are reached largely by a process of deduction, aided by the fact that after the Moors were ousted from power in the 13th century there was a sizeable Muslim population in the whole of the Ricote valley.

Archena after the Christian Reconquista in the 13th century: the Order of San Juan

The Moors remained in power in Murcia until the year 1243, when by the terms of the Treaty of Alcaraz the Muslim leaders capitulated to the forces of Fernando III of Castilla under the leadership of his son Alfonso, later to become King Alfonso X “El Sabio”. At this point the fortress of Archena was initially placed in the hands of a Castilian nobleman named Rodrigo López de Mendoza.

The Treaty provided for Muslims to continue living peacefully in the kingdom of Murcia with religious freedom and equal rights to the Christians, but a gradual erosion of these privileges led to an uprising on the part of the “Mudéjars” (the Muslims who had chosen to remain in Spain) in 1264. This rebellion was successfully quashed within two years by the forces of Jaime I of Aragón, and although the treatment received was distinctly harsh many Mudéjars chose to remain in Murcia rather than fleeing to the still Muslim kingdom of Granada.

But the effect of this discontent was enough to send the population of Archena and other towns downwards, making it difficult to maintain agricultural activity at its previous level.

Another of the consequences of the way in which the Reconquista of Murcia was achieved was the donation of land and towns to those who had helped in the armed struggle, principally the military-religious orders who had joined the cause more or less as mercenaries. In this case the most relevant of these was the Order of San Juan de Jerusalén, which was entrusted with both Calasparra and Archena in 1244 by the grateful monarchs who had enlisted their services, and subsequently their land in Murcia was administered by an “Encomienda” in Calasparra and a Sub-Encomienda in Archena.

The rule of Rodrigo López de Mendoza in Archena had lasted for just one year.

In one form or another the Order of San Juan persisted in Archena until the 19th century, except for a brief hiatus in the 15th when Alonso Fajardo “El Bravo” briefly wrested the town from their control. A medieval social organization similar to the feudal model was thus maintained well into what in northern Europe is considered the Modern period, with the Order remaining “lords of the manor” through the wealth generated both from their own assets (mainly land) and through tithes and taxes imposed on the residents.

Little now remains as testimony to the centuries of subservience to the Order of San Juan in Archena, other than the symbol of the distinctive cross of the Order on the official coat of arms and on the main doors of the parish church.

But the medieval-style local economy was different from others in Murcia in one key respect: the spa, which was without doubt the most prized of the many natural assets in Archena. The River Segura also played its part, and the remains have been discovered of two water wheels dating from the 12th and 13th centuries which would have been used to lift drinking water onto the banks.

For the first 250 years or so after the Reconquista of Murcia Archena was one of many towns where the way of life was dominated and determined by its location close to the border with the (still Muslim) kingdom of Granada, under the rule of the Nazrid dynasty from 1230 onwards. At the same time, there were military threats deriving from the conflict between the Christian kingdoms of Aragón and Castilla.

The resulting de-population of the area was accelerated by internal conflicts within Murcia, particularly those between the Fajardo and Manuel families, outbreaks of plague in 1348 and 1395 to 1396 and periods of agricultural crisis and famine. In short, Archena, like other parts of what is now the Region of Murcia, was an inhospitable place to live in the 14th century and few chose to do so.

But it was against this backdrop that the members of the Order of San Juan consolidated their local power base, and during the 15th century the Casa Grande, which is now the Town Hall, was built as a grain store and a nerve centre from which tight financial and administrative control were enforced.

The Late Middle Ages in Archena

At least one of the disadvantageous aspects of life in Archena and the Region of Murcia was cancelled out in 1492, when Granada fell and the Nasrid dynasty, along with all other Muslims, were expelled from Spain by the Catholic Monarchs. This led to relative tranquillity in what had previously been frontier settlements, a climate which gradually brought about an increase in agricultural activity as more people chose to live in a part of the Iberian Peninsula which for two and a half centuries had been considered eminently dangerous.

At this time the most important crops and products here included rice, barley, millet and olive oil, and during the 16th century the town of Archena and its agriculture became far more established and productive. There was a tavern selling wine and vinegar, a butcher and a spice merchant, and two mills were used to grind rice and flour, both belonging (of course) to the Order of San Juan.

Again, though, hard times were around the corner, and in Archena the 17th century began with further de-population. This time one of the main causes was the deportation of the “Moriscos”: these were the descendants of the Moors who had chosen to remain in Spain after 1492 and convert to Catholicism, and in 1609 King Felipe III, suspecting certain Morisco leaders of plotting with the King of France to bring about a revolt in Spain, decreed that they should be expelled.

This resulted in 272,000 being shipped out of Spain over a period of seven years, and many of the 16,000 or so who were forced to leave Murcia were inhabitants of the Ricote valley. It is reported that around half of the 86 families in Archena which in theory were to be deported managed either to escape capture or to return shortly afterwards, but nonetheless the resulting shortfall in farm labourers was a serious setback for agricultural production, and any signs of timid recovery were reversed quickly by an outbreak of plague in 1648 and other natural disasters.

Despite this, the Order of San Juan was active in ploughing new land and making it cultivatable, and also invested in water supply infrastructures for irrigation and drinking water purposes, enabling Archena to slowly haul itself out of the period of crisis.

Archena in the 18th and 19th centuries: the start of the Modern period

As was the case for almost all towns in Spain the first years of the 18th century marked a return in Archena to hardship and food shortages, this time as a result of the conflict known as the War of the Spanish Succession. Archena was not greatly involved in the war in a military sense, but a company of French troops was stationed in the town and this placed a heavy strain on economic and agricultural resources.

But once the war had ended there was at last a period of prolonged prosperity, which is reflected in a significant increase in population from just 136 in 1703 to 1,128 in 1797. Most of the local families still made their living in agriculture, with new fields now being irrigated and used following the initiative of the Order of San Juan the century before, and the climate of economic growth and relative stability saw the start of the construction of the baroque parish church dedicated to San Juan Bautista.

However, yet again the start of a new century meant more suffering in Spain, and the early 1800s were marked by the Peninsular War, in which Napoleon Bonaparte fought for control of the country against Spanish forces strengthened by allies from Britain and Portugal. During this conflict the role of Murcia was principally a strategic one, its main function being as a port of call for troops on the move between Andalucía and the eastern coast and as a food supplying region for the Spanish troops.

Archena joined the spirit of the age by forming its own local guard, the “Junta Local”, to fight against the French invaders, but the effects of the war were again far-reaching and an economic downturn ensued. In addition, the spa was converted into a hospital for those wounded in battle, a series of poor harvests brought hunger to the town, and an outbreak of yellow fever in 1811 set the seal on a miserable start to the 19th century.

The next major event in Spain with an immediate effect on Archena was the disenfranchisement of the religious orders, which involved their lands and properties being confiscated and sold off to the highest bidder at auction. This was achieved through a series of parliamentary bills becoming law, most of them in the first half of the 19th century, and in Archena resulted in the properties belonging to the Order of San Juan being confiscated in 1850.

As a result, the land and spa of Archena were acquired by the Marquis of Corvera, who promptly ceded them to his brother the Viscount of Rías, and eventually the descendants of the latter passed on the farmland they inherited to the tenant farmers who worked it, keeping only the park and the ancestral home on the bank of the Segura for themselves.

The importance of the thermal spring in Archena was such that 95 per cent of the proceeds from the auctioning of the Order of San Juan’s assets came from the spa, and only the remaining 5 per cent from other properties.

Under the ownership of the Viscount of Rías, the baths became a genuine big business, and the original Hotel Levante and the Casino date from the years during which he was in charge, as does the on-site church of the Virgen de la Salud. In 1860 the number of guests had reached 5,000 per year: that might not seem like many, but it must be borne in mind that travel was still difficult and that therapeutic treatments generally lasted nine days, and as a result each guest stayed for a considerable period of time.

By the end of the 19th century and the early 20th Archena was the busiest thermal spa in Spain, and visitor numbers were boosted by the construction of the military residence due to the apparent effectiveness of the waters in treating gunshot wounds.

The second half of the century saw a series of revolutionary changes in Archena following the end of the feudal-style society which had existed under the Order of San Juan. Liberals and Conservatives alternated in power in the Town Hall, and the economy was given a huge boost by the arrival of the railway (initially on the Murcia-Cieza line) in 1864. This enabled farmers to export their products to the rest of the country, and also led to the setting up of fruit and vegetable canning factories and to the beginning of the first golden age of the spa, as visitors suddenly had at their disposal an easy and relatively quick way of reaching the hotels there.

The number of food shops in Archena rose from one in 1803 to seven in 1834 and 14 in 1855, and further measures of growth came in 1865, when both the Casino (which wasn’t finished until the end of the century) and the bridge over the River Segura were opened, the latter substituting the old ferry boats which had previously been used to cross the river. By 1878 another church, the Ermita de la Virgen de la Salud, was open in the spa, but the burgeoning population gradually found it harder to make a living and many emigrated, initially to the north of Africa and then onward to the “promised lands” of Barcelona or America.

Thus, at the start of the 20th century the population was still only 4,500, although it had grown to well over 7,000 by the start of the Spanish Civil War in 1936.

The Spanish Civil War in Archena

During the war the Republican forces established a tank base in Archena, training operators in the handling of armoured vehicles purchased from Stalin in the Soviet Union and from France before they were sent into combat elsewhere. The base was active until the end of the Civil War in 1939, and Archena was chosen due to its being a long distance from the front line, its natural protection provided by the mountains around the Ricote valley, its relative proximity to the key port of Cartagena and its location on the main highway to Madrid.

The first Soviet tanks arrived in Cartagena on 12th October 1936 along with 51 instructors, and commanding officer Colonel Seymon Moisevich Krivosheim was instructed by the Spanish Communist Party to take them by rail to Alguazas and from there by road to Archena. En route the tanks were concealed under olive trees in order to avoid detection and air strikes by the Nationalist forces.

Meanwhile, potential tank drivers were recruited from among those already driving taxis, buses and trucks in Madrid and Barcelona, and some of these were among those at the wheel when the Soviet tanks entered the fray at the Battle of Seseña in the province of Toledo on 29th October 1936.

More tanks arrived in Cartagena in 1937, followed by a last consignment on 13th March 1938, but by this stage the Nationalist victory was in sight and Soviet support for the Republicans was withdrawn. But Archena had served as a training base for many different disciplines during the combat, tank driving practice was held in the Ricote valley, and military theory classes were given by the Soviet instructors in the Casino of Archena. The base was also used by USSR counter-espionage staff, a military hospital was in service next to the spa and air-raid shelters were created underneath the spa.

Thus there was no actual fighting in Archena, but the town was heavily involved in the Civil War, and when it ended this brought about considerable hardship, as it did in the rest of Spain. In fact, for many years after the war malaria was common in the town, and the population figures and the local economy did not reach pre-war levels again until the 1960s.

As for the spa, after passing into the ownership of the Marquis of Perinat in 1923 and surviving the Civil War it was purchased in 1950 by industrialist Nicasio Pérez Galdó, whose descendants still own it.

Contemporary history

Much of the growth of Archena since 1950 can be attributed to the efforts made by Nicasio Pérez to establish the spa once again as one of the most important in Spain: the first of the thermal water swimming pools was built in 1958, and since then the Balneario has been one of the main reasons for the town being known throughout the rest of the country.

Agriculture benefitted from the construction of small-scale desalination plants and the opening in the 1970s of the Tajo-Segura water supply canal, which led to an increase in irrigation farming. But the water supply problems in this part of Spain are endemic, and the growth of agriculture was limited to the point where nowadays most of the population no longer depend upon it for their livelihoods.

The population has almost doubled to just under 19,000 since 1970, though, and now many of them are involved in service industries or commute to work in other areas.

Click to see further information about the municipality of Archena

article_detail

Contact Spanish News Today: Editorial 966 260 896 /

Office 968 018 268