-

Welcome To

Welcome To Molina de Segura

Molina de Segura

Welcome To

Welcome To Molina de Segura

Molina de Segura

Welcome To

Welcome To Molina de Segura

Molina de Segura article_detail

article_detail

Welcome To

Welcome To Molina de Seguraarticle_detail

Molina de Seguraarticle_detailA history of Molina de Segura

Strategic location and natural resources first drew prehistoric settlers to Molina de Segura

In terms of population Molina de Segura is the fourth largest municipality of the Region of Murcia, and is generally viewed as a comfortable place to live and work, or at least to commute into the regional capital just a few kilometres to the south. But few of the 70,000 or so who live here are actually aware that Molina also has a long history, closely interwoven with that of the Region as a whole, and for many centuries has enjoyed great importance on account of the strategic advantages of its location on the eastern bank of the River Segura and the fertile farmland on the plain.

The earliest humans to settle in what is now Spain are known to have lived in this area, drawn principally by the same factors which make it such an important logistical hub today; its strategic location at an important natural crossroads drawn out by the folds of the sierras, mountains, plains and valleys cut by nature, surrounded by flat fertile land and with an ample water supply.

Prehistory

In the municipality of Molina de Segura – it has to be remembered that this covers an area of 170 square kilometres, and is by no means restricted to the town itself – there is ample proof of pre-historic habitation, with numerous archaeological sites having yielded artifacts from the Stone Age and the Copper Age.

The oldest of these remains belong to the Paleolithic (or Stone Age), a period which broadly encompasses 2.5 million to 10,000 years BC.

During this period an early human predecessor, Homo habilis, is known to have first used stone tools, and these remained the principal source of material for cutting and hunting until the end of the Pleistocene which was around 10,000 BC.

This is such a vast period that it is divided into several segments of time as the various forbears of humankind evolved and the landmarks which so clearly define the development of modern man occurred; the discovery of how to make and use fire for example, which is believed to have taken place around 790,000 years ago when Homo erectus was predominant took place in what is commonly referred to as the Lower Paleolithic.

It was during the Lower Paleolithic, when settlers were first attracted to what is now Molina de Segura between the mountains of the Sierra del Lugar and La Espada, on the banks of the River Segura, and evidence has been found that silex, or flint was worked in Fenazar during this period.

However, the most significant evidence of early habitation relates to the period known as the Middle Paleolithic, which is defined by the appearance of Homo sapiens, which is first found around 200,000 BC.

At this same time Neanderthals were also evolving, and although they became extinct as a separate definable species around 40,000 years ago, were also living in Europe. Of course, the debates continue as to how much interaction took place between Homo sapiens and Neanderthals and whether Homo sapiens were ultimately responsible for the demise of the Neanderthals, in spite of the fact that there is clear evidence of interbreeding between the two distinct species.

By this point Homo habilis had disappeared.

Techniques of stonework employed by the Neanderthals are also distinct, and Neanderthal sites show a manipulation of flint that has resulted in the classification of the period between 95,000 BC and 35,000 BC as the “Mousterian culture” of the Middle Paleolithic.

The name is simply taken from the “Le Moustier” site in the Dordogne region of France where the technique used to make flint tools using a flint knapping technique which has become known as the Levallois technique (due to the discovery of tools in the Levallois-Perret suburb of Paris,) was definitively associated and identified. Since the first discoveries of the technique used were classified, it has become clear that the techniques were also copied by early Homo sapiens, although here in Molina de Segura, the Mousterian sites which relate to this period and date between 95 and 35,000 BC, appear to be Neanderthal.

In Molina de Segura sites adjacent to a rambla in the area now known as Las Toscas contain remains of clear manipulation of flint using the Levallois technique, which involves chipping flakes from around the edge of a flint stone to create a pointed, multifaceted piece of flint. These had many uses and could be made into scrapers, tools for cutting and weapons.

Other sites relating to the Mousterian era have also been found in El Fenazar, El Montañal in the pedanía of los Valientes and in the Rambla Salada, the technique used again appearing to indicate the presence of Neanderthals.

By the time prehistory reached the next period, known as the Neolithic, or New Stone Age, the Neanderthals had disappeared as a definable and separate species, Homo sapiens, or modern man, progressing from life as a hunter-gatherer, to start farming both animals and crops, was now the only “human” species remaining.

The very earliest evidence of sedentary farming takes us forward to around 12,000 BC, and between the period of 10,200 and 2,000 BC the techniques of farming spread throughout Europe as modern man learnt how to sow crops and rear animals domestically.

Neolithic ceramics have been found in Molina de Segura in the area around the Fuente Setenil.

The Argarics

Click for full information about the Argaric culture.

Between 2200 BC and 1550 BC the Argaric Culture was present in what is now South - eastern Spain, the culture occupying multiple sites in the Region of Murcia, Almería, Granada, Alicante and Jaén. This period falls within what is widely known as the Bronze Age, a stage in technological development which co-incides broadly with other populations developing along the same lines within Europe: Wessex and Armorican Tumuli, (Hilversum Culture of Central Netherlands, Belgium and Northern France, broadly 2000BC to 1400 BC) Polada (Italy, 13th and 14th century BC) and Unetice (2300-1600BC, based around the Czech Republic, western Poland, and Southern and central Germany).

The Bronze Age denoted an era in which mankind had developed metallurgical skills which enabled him to build substantial settlements. Advances in metallurgical technologies made the agricultural processes of production easier, and individuals were able to develop specialist skills, opening up the way for trade, social development and structure, territorial organisation and definition, emergence of funeral rites and the expansion of the population.

In Molina de Segura the Argarics were occupying strategic sites alongside natural resources on outcrops near to water and ramblas in the Sierra de Lugar and Sierra de la Pila.

Argaric tools and ceramics are uniform throughout the many sites in which they have been found, indicating a clear level of control over measurements and communication in what was a clearly hierarchical, specialised and structured culture, in which goods were clearly manufactured in one site and distributed to others. In Molina de Segura barquiform grain mills made from volcanic rock have been found, along with smooth, uniform Argaric ceramics, and various tools, including a cutting scythe made by inserting flakes of flint into a piece of curved wood.

Many of the archaeological discoveries made in Molina can be seen in the Museo Carlos Soriano in El Llano de Molina, while others are held in the collection of the regional archaeological museum in Murcia City.

The Iberians

The Iberian tribes were dominant in what is now Spain from approximately the end of the 6th century BC

until the arrival of the Romans in the 2nd and 2st centuries BC, but there is no evidence of a large Iberian settlement in Molina de Segura, the theory being that Molina was a transit point for those travelling between the more important towns in Baños de Fortuna, Archena and El Cigarralejo in Mula.

until the arrival of the Romans in the 2nd and 2st centuries BC, but there is no evidence of a large Iberian settlement in Molina de Segura, the theory being that Molina was a transit point for those travelling between the more important towns in Baños de Fortuna, Archena and El Cigarralejo in Mula.However, Iberian remains have been found in the area close to the point on which the Moors built their fortifications, indicating that there may have been a settlement on the same strategic point now occupied by the MUDEM museum in the town centre.

Several small Iberian settlements have been found in Molina de Segura, principally in the countryside of Fenazar, Los Valientes, La Hornera, Fuente Setenil and Rambla Salada, located on small elevations alongside water resources.

Click for more information about the Iberians.

The Romans and Carthaginians in Molina

The discovery of Carthaginian coins at the El Fenazar site indicates that the communications routes which were later to be adopted by the Romans were already in use before they arrived in south-eastern

Spain, connecting Lorquí, Ceutí, Molina and Abanilla in the 3rd century BC. One of these routes follows the River Segura as it passes through Molina de Segura and the outlying districts of La Ribera, Torrealta and El Llano, while another is the one which runs across it from Elche, Alicante and Orihuela towards Archena.

Spain, connecting Lorquí, Ceutí, Molina and Abanilla in the 3rd century BC. One of these routes follows the River Segura as it passes through Molina de Segura and the outlying districts of La Ribera, Torrealta and El Llano, while another is the one which runs across it from Elche, Alicante and Orihuela towards Archena.This effectively places Molina at a crossroads, and as such it was much used by both the Carthaginians, who ruled Cartagena for 18 years from 227 BC, and the Romans, who ousted their predecessors in 209 BC. It is thought that the Romans placed a fortress at the crossroads, more specifically at the site of the old church in Molina, and alongside it is natural to suppose that there would have been lodgings, food and animal feed available for weary travellers. Much of this, though, is speculation, as the actual relics found merely confirm the Romans’ presence, and there is little tangible evidence of anything significant apart from agricultural activity in the area.

In fact, the most probable scenario is that there was a “villa” from which local agriculture was administered and managed, at the same time providing a good vantage point over the course of the River Segura. The remains of other villas have been found in the Molina countryside, and indeed the name of the town is derived from the Latin for “mill”. The Moors maintained the nomenclature, adapting it to Mulinat-as-Sikka (the mill on the road), and after the Reconquista of the area in the 13th century the Christian forces in turn corrupted this to “Molina Seca”.

Similarly, there is evidence to suggest that around during the Roman occupation the first settlements arose on the hill where the castle of Molina was later built: ceramic fragments from the 2nd century BC have been unearthed in the area, and at the same time more ceramics dating from the height of the Roman Empire to the 3rd and 4th centuries AD have been found along the communications routes which crossed in Molina.

It has to be said that our detailed knowledge of these routes comes not directly from Roman sources but to a large extent from Moorish geographers writing around a thousand years later: they refer in fact to three roads, one running along the course of the Segura and north to Complutum (Alcalá de Henares, in Madrid), another from Santa Pola and Elche to Archena, and a third from the Segura valley to Yecla and Jumilla in the north of the modern-day Region of Murcia.

The Romans effectively disappeared as a definable population from Spain as the Empire began to collapse in the fourth century AD, and after an interlude lasting three or four centuries the next civilization to leave a lasting mark on south-eastern Spain was that of the Muslims from north Africa.

Molina under Moorish rule

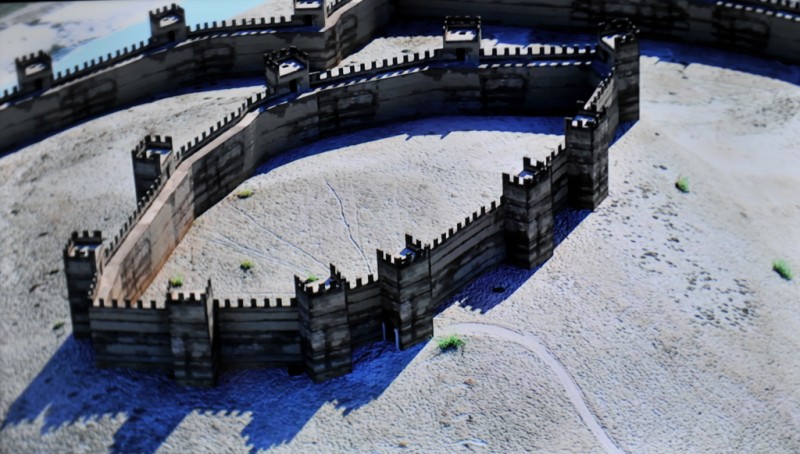

There may be some doubt over whether or not the Romans actually founded a town on the site of Molina, but no such uncertainty exists over the Moorish settlement here. The remains of their fortress have been unearthed in the Barrio del Castillo, where the Mudem museum tells the story of the building, and this fortification is known to have been successful in resisting the troops of the Umayyad Caliphate in the year 896.

The Moors effectively took control of what is now the Region of Murcia from the Visigoths in the year 713 through the Pact of Tudmir, and were to remain for over 500 years, definitively influencing the landscape, agriculture and society of medieval Spain. Molina is not one of the townships mentioned in the Pact, but it was during their presence that the town became one of importance, and various other settlements are known to have existed within the boundaries of the municipality, most of them agricultural in nature.

The first actual mentions of Molina in Moorish documents come from Córdoba historian Ubn Hayyan, who includes the town under the name of “Maniya” in an account of troops being sent to quash a revolt during the reign of Abd Allah (888-912). In 1085 geographer al-Udri uses the name “Mulina” to refer to the town 11 kilometres north of Murcia on the road to Siyasa (Cieza) and onwards to Toledo. He also makes reference to the road from Lorca to Mulina, indicating that Molina was still on an important crossroads of major routes.

By the 11th century the town was sufficiently important for King Alfonso VI of León to set up camp here and call for the help of Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar, El Cid, to defend the city of Aledo in 1096 (or, according to some accounts, 1088). Unfortunately, though, the King ran out of patience while waiting for El Cid to arrive, and left without him, interpreting his late appearance as a snub.

In the 12th century there is further reference to the town on a description of the route from Murcia to Segura de la Sierra (in the modern province of Jaén), and this time mention is made of the “hisn” or fortress.

It has been established as a result of archaeological digs that the hisn of Molina existed prior to the walls which encircled and protected the town, these latter having been added in the late 12th century as the conflict between the Moors and the Christian forces in the north of the Iberian Peninsula began to escalate. At this point it became necessary to protect the population living outside the fortress, and thus the two typical areas of the fortress were created: the keep itself, and the fortifications to protect and enclose the population living around it.

No complete picture has emerged regarding either structure, but a lot has been gained from recent excavations since the remains of the wall were discovered in 2004, underlining the extent to which the history of Molina has literally been lost from sight as the town has grown.

A visit to the Mudem museum allows one to learn about both the structure and features of the town’s defences in the Middle Ages and the history of Molina until the 15th century, and the stretch of wall itself inside the building features a nine-sided tower – the only one of its kind yet discovered in Murcia - and the typical “double hairpin” entry gate, which slowed down potential attackers and allowed defenders to attack them from above.

Elsewhere it is thought that there was a hilltop fortress here as early as the 9th century, at what is now the Mirador del Castillo viewing point, where the remains of a four-sided tower have been supported by a 12-metre wall.

As for the wall around the town, it is known that it was punctuated by lookout towers approximately every 20 metres, and that it was extensively reformed in the early 13th century as tension mounted prior to the eventual Reconquista of Murcia from the Moors by the Christian forces of Castilla. At this point the height of the 2-metre-thick defensive structure was raised to approximately 8 metres, while at the same time it was made stronger by a 7-metre moat outside it, and only slight further modifications are known to have been made after the Reconquista.

There were at least two gates, one at the end of Calle Consolación, leading towards Murcia, and the other which was found during the excavation work at the Maximino Moreno factory, which has subsequently become the museum: this latter entrance is known as the “Puerta del Campo”, the gate to the countryside.

Other fragments of the medieval wall are those in Calle Pensionista, where one part has been incorporated into the Molina de Segura tourist office and another is in the basement of a residential building, and in the square in front of the Iglesia de Nuestra Señora de la Asunción.

In short, the Hisn of Molina was almost certainly not one of the most important in Murcia, being home to only a small population and not being the centre of any administrative district, but due to its strategic location the defences and structural elements are similar to those of towns which were far more significant at the time, including Murcia and Orihuela. Thus it formed part of a ring of defensive installations around Murcia which also included the fortresses of Monteagudo and Tabala.

The construction of these fortifications coincided with the reign of Ibn Mardanis, otherwise known as the Rey Lobo or Wolf King (1146-72), during which the Region of Murcia reached its highest splendour during the centuries of Moorish rule. “Mulinat-as-Sikka” benefitted, not only through the reinforcement of its defensive but also throught the creation of a weir in the course of the River Segura to provide irrigation in La Algaida. This weir is still at the centre of the irrigation system in the surrounding countryside, and although much of what the Moors did for agriculture in the area consisted of modifying and improving Roman infrastructures this was an important innovation.

The Wolf King maintained a mainly independent kingdom in which Muslims and Christians were all welcome, basing his kingdom in the castle and palace of Monteagudo, and this remained the situation until well into the 13th century.

The Reconquista: Mulinat-as-Sikka becomes Molina Seca

But in 1243 that all changed, as the Moorish defenders were defeated by the troops of Fernando III of Castilla and power was transferred into the hands of the Christian forces he led. The transformation of the whole of Murcia was not immediate, and in Molina the changeover was not fully completed until 1266, when the town and castle were incorporated into the territory of Murcia along with Mula and Ricote.

At this point the Arabic name of Mulinat-as-Sikka mutated into Molina Seca, by which the town is referred to in documents until the 15th century. At the same time the “Heredamiento Agrícola” was created to administer agriculture in the huerta (the fertile flood plain of the Segura), and under the rule of Fernando III’s son Alfonso X “El Sabio” the town was entrusted to a series of administrators. Alfonso also took control of numerous castles and fortresses, including the one in Molina.

As a consequence of its surrendering without putting up too much of a fight Molina was treated relatively well by its new Christian overlords, who allowed both Christians and Muslims to continue with their lives and beliefs: in fact, the Muslims were still theoretically under the rule of their own sovereign, Ibn Hud. However, a Muslim uprising in Murcia was ruthlessly quashed in 1264, and the somewhat uneasy tolerance of the community diminished as a result.

Two years later, the lands of Murcia were definitively taken by King Jaime I of Aragón, and this marked the start of a series of long-lasting conflicts between the regional capital and Molina. In 1266 Alfonso X recognized Molina as an independent township, but later the same year he appears to have changed his mind and placed it back under the control of its largest neighbour, a decision which was partially reversed in 1272.

But in 1283 the pendulum swung the other way again as a punishment for Molina siding with Alfonso’s son Sancho in a dispute over the succession of the Crown. This punishment was lifted just eight days later, and the following year Sancho became Sancho IV of Castilla.

There soon followed a decade of subjugation in Murcia to the rule of the Crown of Aragón as a result of succession issues in Castilla, but in Molina as in other areas this was not greeted with much enthusiasm. The authorities in Murcia, Cartagena, Lorca, Alicante, Mula, Guardamar, Molina Secca and Alhama all signed a pact to defend their identity, although this was not a success and from 1296 until 1304 the whole of Murcia remained under the rule of Aragón.

Molina and Don Juan Manuel

During these to-ings and fro-ings Molina had been under the administration of a series of men, but in the 14th century it ended up in the hands of Don Juan Manuel, one of the wealthiest, most influential and most powerful men of the age.

Juan Manuel ruled in Murcia as if the city were his own, and when he took control of Molina many of his supporters moved to the town. This was achieved in 1312, when he waived a debt owed by King Fernando IV in exchange for control over Molina, another decision which was certainly not welcomed by the inhabitants.

The new effective owner of Molina bore such a grudge against Murcia and other towns that Molina soon gained a reputation as a home of thieves, and this led to Murcia forcibly taking control of the town once again in 1314. Don Juan returned to power the following year, but there was another revolt against him in 1325 and he fled to Orihuela before yet again falling foul of his superiors when he plotted against King Alfonso XI after the latter declined to marry his daughter.

Molina was placed under the administration of Pedro López de Ayala in 1328, but just two years later Don Juan Manuel was back, this time as lord of both Murcia and Molina.

The saga appeared to have ended when Don Juan Manuel died in 1348, but there were disputes over who should take control until his daughter married Enrique II of Castilla, restoring the title of royal township to Molina.

Molina and the Fajardos

Power struggles followed in Murcia between the Manuel and Fajardo families, and in 1395 the town was placed by Enrique III under the administration of the King’s emissary to Murcia, Alonso Yáñez Fajardo, beginning a long association with the Fajardo family which was to bring mixed fortunes to Molina. A series of conflicts and military skirmishes followed, but eventually this gave way at last to peace and relative prosperity.

It was not until 1397 that power over Murcia was effectively transferred to the Fajardo family, and at this point it is clear that the old castle was already in disrepair, as mention is made of the need to re-build it.

Under the rule of the Fajardos, especially Alonso Yánez Fajardo II and Pedro Fajardo Quesada, Molina suffered a series of attacks, many of them originating from the descendants of Don Juan Manuel (the Manueles) in Murcia. Others, though, were the result of infighting within the family: at one point, when Pedro Fajardo Quesada was still under the age of 18 his relative Alonso el Bravo attempted to relieve him of all his titles and possessions, and Pedro fled Murcia to live with his widowed mother in Molina Seca. It was not six years later that royal intervention resulted in a pact being signed by the two men in the Iglesia de Santa María in Molina.

At the same time, it must be remembered that Murcia was still frontier territory, and there were numerous raids from the neighbouring Moorish kingdom of Granada, but in the 15th century a period of relative stability brought peace to Molina Seca, and Pedro Fajardo Quesada was the king’s emissary to Murcia from 1444 to 1482. During this period he controlled not only Molina but also Librilla, Alhama, Mula, La Puebla de Mula, Campos del Río and large parts of Almería under the “Mayorazgo de lso Fajardos”.

This power base was made official in 1438 by Juan II, and was reaffirmed by the Catholic Monarchs in 1489, after the land governed passed into the hands of the Chacón family when Juan Chacón married Luisa Fajardo.

Contemporary documentation relates that although Molina boasted few inhabitants it was an important town by now, and contained not only the fortress but also criminal courts, a bread oven, a tavern, salt flats, olive oil presses and organized irrigation ditch networks. At the same time, it was home to Muslims and Jews as well as to Christians, although this was to change after the definitive expulsion of these religious minorities from Spain with the taking of Granada in 1492.

Molina under the Marquises de los Vélez: the Fajardo line continues

In 1535 the links between the Fajardo family and the town were strengthened still further by Carlos V’s decision to name Luis Fajardo de la Cueva the Marquis of Molina. Members of the clan married into other leading noble families, such as those of Villafranca, Alba, Fernandina and Medina Sidonia, and in general terms they treated the inhabitants of Molina with respect, allowing a social structure to develop which would remain in place barely altered until the 19th century.

It was at this point that the family was awarded the title of Marqueses de los Vélez, confirming their meteoric rise from a newly wealthy clan to one of the most powerful aristocratic families in Spain. The title was first given to Pedro Fajardo Chacón in 1507 by Juana I “La Loca”, 28 years before his successor Luis Fajardo de la Cueva was made Marqués de Molina.

But this is not to say that there was any end to the ups and downs of Molina’s development. As in many other parts of Spain, the expulsion of the Jews and Moors in 1492 led to a considerable drop in the population, and the best of the farmland was acquired by residents of Murcia as owners sold off their rights when they found themselves without labourers to till the soil and tend the crops. The largest single landowner was soon the Jesuit Compañía de Jesús, which eventually took possession of around half of all of Molina’s cultivatable land until 1767, when the Jesuits were also expelled: their land in Molina was then taken over by the Zabalburu family, who retained much of it until as recently as the 1970s.

Even in 1635, almost 150 years after the tumultuous events of 1492, there were barely 100 people living in Molina, and this was far from a wealthy town. Many previous residents had been among the heavily taxed “moriscos” – former Muslims who had chosen to convert and remain in Spain – and when they too were expelled in the early years of the 17th century the local economy suffered the consequences of a depleted workforce.

But by the second half of the century, after the plague of 1648 and the disastrous flood of San Calixto three years later, a recovery was under way both in Molina and in the rest of Murcia. Agriculture still made use of the Moors’ “acequias”, or irrigation ditches, modified by Melchor de Luzón after the flooding to extend further afield, and during the 18th century the population rose from 1,269 to 3,128. The agriculture which provided their livelihoods was concerned principally with cereals, grapes and olives, but there was also textile production (linen and flax) and fruit, vegetables and even rice, until this latter crop was banned in 1725.

In this period another of the most important plants grown was the white mulberry tree, in which locals nurtured silkworms, and the silk industry became the strongest motor behind the growth and increasing wealth of Molina.

This agricultural activity and increased prosperity led in turn to the expansion of the town and the construction of important buildings such as the Iglesia de Nuestra Señora de la Asunción (1765).

The 19th and 20th centuries in Molina de Segura

It was in the early 19th century that the relationship between the Marquises de los Vélez and the town of Molina at last came to an end, and although further floods followed in the latter part of the century, notably in 1879 and 1895, by this time the Zabalburu family were well established as the dominant force in local affairs. Family members occupied the post of Mayor almost permanently as a result of “fixed” elections and prosperity was more or less permanent.

Living up to its name, the town’s economy was dominated by milling – not only of flour, but also of paprika which was grown locally, most of it on the land owned by the Zabalburus and the Heredia-Spínola family.

In addition, as the water supply increased with the construction further inland of the reservoirs of Talave, La Fuensanta, Cenajo and Camarillas, the range of crops widened, and eventually in the early 20th century the advent of industrial processes brought the canned fruit industry to Molina in no uncertain terms.

In 1906 the name of Molina de Segura was officially adopted, and until the middle of the 20th century canning and agriculture continued to be the motors of growth, with products now including peaches, apricots, vegetables, olives and grapes. At the same time sheep farming was also important, but by the 1940s Molina had developed into one of the most important centres of canned fruit and vegetables in the whole of Spain.

Curiously, much of this industrial growth was down to the energies and efforts of just one man, José Hernández Gil, who not only made a fortune and purchased over 140 properties during his career but also fathered 23 children during his three marriages. His numerous descendants set up some of the most important canning companies in Spain, including Conservas La Molinera, Conservas Hernández Contreras (also known by the brand name El Gladiador) and Conservas El Pelícano. All told they owned a dozen or so firms, and 30 factories, not only in Molina but also in Mula, Alguazas, Las Torres de Cotillas, Murcia, Lodosa and Cortes (the last two in Navarra).

The leather industry also became closely associated with the town, and despite the economic crisis of the 1990s Molina continue to grow, with the population rising from 8,000 to 44,000 during the whole of the 20th century. By 2015 the number of inhabitants had risen to over 71,000, many of them in new outlying residential areas such as La Alcayna and Altorreal, and a host of service industries sprang up alongside more traditional businesses including the manufacture of sweets and specialized engineering concerns.

Click for full information about the Molina de Segura municipality in English

article_detail

article_detailContact Spanish News Today: Editorial 966 260 896 / Office 968 018 268

To be listed on the CAMPOSOL TODAY MAP please call +34 968 018 268.

To be listed on the CONDADO TODAY MAP please call +34 968 018 268.

Guidelines for submitting articles to Camposol Today

Hello, and thank you for choosing CamposolToday.com to publicise your organisation’s info or event.

Camposol Today is a website set up by Murcia Today specifically for residents of the urbanisation in Southwest Murcia, providing news and information on what’s happening in the local area, which is the largest English-speaking expat area in the Region of Murcia.

When submitting text to be included on Camposol Today, please abide by the following guidelines so we can upload your article as swiftly as possible:

Send an email to editor@camposoltoday.com or contact@murciatoday.com

Attach the information in a Word Document or Google Doc

Include all relevant points, including:

Who is the organisation running the event?

Where is it happening?

When?

How much does it cost?

Is it necessary to book beforehand, or can people just show up on the day?

…but try not to exceed 300 words

Also attach a photo to illustrate your article, no more than 100kb