Museum of ethnic instruments and the Carlos Blanco Fadol collection in the Caravaca village of Barranda

The Museo de Música Étnica y Colección Carlos Blanco Fadol in Barranda

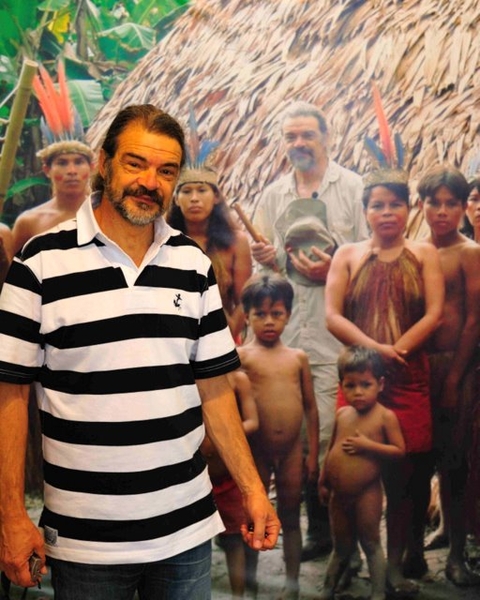

The man responsible for this amazing place is a remarkable man by the name of Carlos Blanco Fadol.

The man responsible for this amazing place is a remarkable man by the name of Carlos Blanco Fadol.

There are many accomplished musicians throughout the world with a passion for music, who are moved to explore their art, learn new techniques, and follow the history of their chosen instrument back far enough to acquire one or two variations which give a different tone, enable them to reproduce authentically historical pieces and play them as they would have been played, or pick up that special guitar with the unique embellishment.

But few take it to the extreme of acquiring 4,000 instruments, as Carlos Blanco Fadol has done.

Carlos has created the largest and most important collection of ethnic instruments in the world and it is housed in in the little village of Barranda, within the municipality of Caravaca de la Cruz, in the Museo de Música Étnica, the museum of ethnic instruments.

The musician and ethnomusicologist travels the world in search of ethnic instruments, more than 70% of which are now no longer played in the communities from which they came, obsessively seeking historical instruments from all cultures of the world, exploring, understanding, gaining knowledge and preserving objects which would otherwise be lost from our cultures forever. What's more, he knows how to play every instrument in this museum himself.

The musician and ethnomusicologist travels the world in search of ethnic instruments, more than 70% of which are now no longer played in the communities from which they came, obsessively seeking historical instruments from all cultures of the world, exploring, understanding, gaining knowledge and preserving objects which would otherwise be lost from our cultures forever. What's more, he knows how to play every instrument in this museum himself.

His astonishing collection contains instruments from around the world, but also throughout history. One of his personal favourites is a set of three tiny bells in a case, which were donated by the regional government of Murcia when they were found during an archaeological excavation. The are more than 2,000 years old.

He also takes pleasure from a gong-dragon, glittering with 24 carat gold, which came from Myanmarin Burma, the Pinsa-yu-pa, and a giant "tan tan", which came from the palace of the King of Madura, Indonesia, accompanied by a photograph of its former owner. He found the gong in an antique shop in Jakarta, when he walked in and couldn't believe that right in front of him was a historical instrument of incredible importance, used to announce the arrival of important visitors to the palace.

He also takes pleasure from a gong-dragon, glittering with 24 carat gold, which came from Myanmarin Burma, the Pinsa-yu-pa, and a giant "tan tan", which came from the palace of the King of Madura, Indonesia, accompanied by a photograph of its former owner. He found the gong in an antique shop in Jakarta, when he walked in and couldn't believe that right in front of him was a historical instrument of incredible importance, used to announce the arrival of important visitors to the palace.

But although there are incredibly impressive pieces and collections, many of which have been donated by governments internationally, there are also simple everyday instruments here which date back through the centuries and weave history into everyday life.

There are pieces used in religious ceremonies, slave instruments which made repression and brutality more bearable, pieces used in magic and witchcraft, instruments of war which were marched into carnage and death during military battles, instruments employed to find love and those which belonged to wandering minstrels, earning a living from the pleasure they gave.

There are also instruments from Murcia, the simple stringed instruments which accompanied fiestas and celebrations and religious events in the past.

There are also instruments from Murcia, the simple stringed instruments which accompanied fiestas and celebrations and religious events in the past.

Visitors are offered headphones to listen to how the pieces sound as they move from one case to another, experiencing the sounds made by flutes made from bone, nutshell rattles and exclaiming even a simple hollowed out piece of wood as they travel through the world of music.

Perhaps the most moving part of the museum is an area dedicated to one of the most personal projects with which Carlos has been involved, the reconstruction of two instruments which come from deep in the heart of the Amazon. 30 years ago he had collected two ceremonial instruments, the ruuhuitu macho (male) and the ruuhuiti hembra (female), which were used for ceremonial purposes, but he later discovered that they had disappeared altogether from the culture of the Yaguas tribe in the Amazonian heart of Peru.

Perhaps the most moving part of the museum is an area dedicated to one of the most personal projects with which Carlos has been involved, the reconstruction of two instruments which come from deep in the heart of the Amazon. 30 years ago he had collected two ceremonial instruments, the ruuhuitu macho (male) and the ruuhuiti hembra (female), which were used for ceremonial purposes, but he later discovered that they had disappeared altogether from the culture of the Yaguas tribe in the Amazonian heart of Peru.

Carlos resolved to return the instruments to the people of the tribe and went back to the settlement to not only re-introduce the instrument, but also teach the villagers how to make the pieces themselves and safeguard their heritage while around them acres of irreplaceable trees are felled. A fascinating documentary is shown in the museum which follows this journey, the collection of materials from the forest, clearance of a work area and construction of the instruments using techniques employed for centuries to create items used in everyday life. This is fascinating for us, as we live in world where it is easy to take the manufacture of everyday essentials as a consumer right, sparing no thought for the processes employed throughout history.

In this tribe the average life expectancy is only 45, so he chose his pupils carefully from amongst the younger tribe members to ensure that the knowledge of how to make these instruments remain with them, hopefully for at least 50 years. But for him, the most emotional moment came when the new instruments were tested: "It made the hairs on the back of my neck stand up when I heard the sounds of these lost instruments resonating through the jungle. To have been able to contribute this miniscule grain of sand to the preservation of the Amazonian culture was very moving for me."

This is the motivation which drives him to collect and preserve instruments which would otherwise disappear, and as a result the collection has outgrown the museum, with storerooms stuffed to the ceiling with his ever-increasing acquisitions. Only around 5% of his entire collection is on display at any one time due to space restrictions, so has published a book which documents his collection of instruments and discusses the development of music throughout the centuries.

This is the motivation which drives him to collect and preserve instruments which would otherwise disappear, and as a result the collection has outgrown the museum, with storerooms stuffed to the ceiling with his ever-increasing acquisitions. Only around 5% of his entire collection is on display at any one time due to space restrictions, so has published a book which documents his collection of instruments and discusses the development of music throughout the centuries.

The book is on sale at the museum in Barranda and is an absolute essential reference for anyone with an interest in historical and ethnic instruments.

So what is he going to do with his vast collection?

There has been talk of opening another museum in America or in a different part of Spain, but in the meantime Carlos continues to add to the collection and develop his own instruments, incorporating a variety of techniques and his intimate knowledge of the creation of music.

Even the chain in the centre of the reception is an instrument, filtering the rain from the roof above. As the water runs down the chain when it rains it makes a tinkling sound, the plan being to add bells or chimes to create real music with this one day.

Please visit this museum and support the conservation of our musical heritage.

Address: Calle Pedrera, Barranda (Caravaca de la Cruz)

Telephone: 968 738491 / 968 705620

Opening times:

Weekdays 10.00 to 14.00 and 16.30 to 18.30

Saturdays 10.30 to 14.00 and 16.30 to 18.30

Sundays 10.30 to 14.00

Admission charges

General: 3 euros

Children aged 6 to 14, disabled and school visits: 1 euros

Over 65s and groups of 25 or more: 2 euros

Students: 1 euro

Children under 6: Free

Groups are welcomed. Please call 968 738 491 for bookings.

Other

There is a leaflet in English available and many of the staff also speak English.

Access is good for those of limited mobility.

Further information about what to see in Caravaca and the Holy Jubilee Year in 2024 is available from the tourist office (Plaza de España, 7, telephone 968 702424, email turismo@caravacadelacruz.es).

Or for more local information, including the Holy Jubilee Year as well as local news and what’s on, go to the home page of Caravaca Today.