Why it is so difficult to solve the current problems in the Mar Menor

The problems faced by the Mar Menor are caused by a complex combination of factors, making easy solutions equally difficult to find

Anyone with even a passing interest in current affairs in the Region of Murcia and the Costa Cálida will be aware that the Mar Menor, for years the jewel in the crown of the tourism sector of the regional economy, has become a topic of heated debate.

The events of the last four years have accelerated a deterioration in the marine environment of the lagoon about which warnings have been issued by environmentalists for the best part of 40 years, and which resulted in the water of the Mar Menor turning green in colour in 2016 as visibility was reduced. Three years later, the improvement in water quality was shown to be a false dawn in September 2019, when in the aftermath of the heaviest “gota fría” storm for at least half a century the arrival of massive quantities of floodwater clouded the water brown, and then brought about an episode of anoxia (or lack of oxygen) which decimated the marine fauna including fish and crustaceans.

In this context it is a source of great frustration to many people that the regional and national governments, and different political parties, seem unable to agree on what action to take in order to protect and regenerate the lagoon. At times it seems that their priority is to blame their political opponents rather than to set about improving the situation.

But to be fair to the politicians, administrators and legislators, the processes which have combined to cause this situation are complex, inter-related and deep-rooted, and the way to go about halting or reversing them is far from clear.

What follows is an attempt to identify, summarize and explain some of the many factors which have contributed to the current situation facing the Mar Menor. The intention is not to propose a clear route map leading to the complete recovery of the lagoon – if that were possible then all parties concerned would have agreed on it by now – but to enable readers to more clearly understand the complexity of the current situation.

- THE MAR MENOR

10 million years ago the Mar Menor, now the largest saltwater lagoon in Europe, was a large, open bay on the Mediterranean coast of the Iberian Peninsula. But in geological terms those were eventful times in this part of the world, and as sediment made its way into the sea along rivers in what is now known as the Campo de Cartagena a series of volcanos formed, some of them giving rise to the plug of El Carmolí and the islands which still remain in the lagoon: Isla Grosa, Isla Mayor or Isla del Barón, Isla Perdiguera, Isla Ciervo, Isla Sujeto and Isla Redonda.

Much later, approximately 2 million years ago, the bay was almost completely enclosed between the southern end in Cabo de Palos and the northern extreme in San Pedro del Pinatar by a long sand bar which accumulated and connected various of the volcanic and other outcrops including El Pedrucho, El Estacio and Punta de Algas, all but isolating the resulting lagoon from the rest of the Mediterranean. That sand bar is La Manga del Mar Menor, and it was interrupted only by a series of channels called “golas” which allow water to flow between the Mar Menor and the Mediterranean.

By as recently as 2,000 years ago these golas were sufficient to ensure that the water in the shallow lagoon – the maximum depth is under 7 metres although it occupies an area of around 180 square kilometres – was replenished and renewed on a regular basis, but at the same time they were narrow enough for the marine environment on the inland side of La Manga to be radically different from that on the Mediterranean side. The Mar Menor was significantly warmer than the Mediterranean and the level of salinity was far higher: in the first half of the 20th century it was measured at 55 PSU (Practical Salinity Units) as opposed to the 38 PSU of the western Mediterranean.

This in turn led to the development of a unique ecosystem in which species well adapted to warm saline water thrived but others from outside the lagoon found it difficult to survive, and when civilizations from elsewhere in the Mediterranean began to colonize the south-east of the Iberian Peninsula the Mar Menor quickly became a source not only of salt but also of the salted fish products for which it is still renowned. Similarly, in more recent times the famed prawns of the Mar Menor became a favourite in the fish markets of Madrid as soon as reduced transport times made it possible for them to reach the capital fresh!

The Romans used the Mar Menor as a shelter for transport ships, the Moors as a rewarding fishing ground and the Christian monarchs of the Middle Ages as a favourite hunting area, where the woods in the countryside were still home to large populations of deer and other animals, but in the 16th century the pine, oak and yew forests were felled in order to provide fuel for three smoking towers in La Manga and another in Cabo de Palos.

Nowadays this would be viewed as an environmental tragedy or even a crime, but in the Mar Menor there was far worse to come in the 20th century.

- MINING IN THE SIERRA MINERA

First, though, it is advisable to take a long backwards step in time to the centuries before the birth of Christ.

One of the reasons that the Romans considered the conquest of Cartagena to be so important was the mineral wealth of the mountains in what is now known as the Sierra Minera, just to the south of the Mar Menor. Before the Romans ousted the Carthaginians from the city in the third century BC the area had already been mined for silver, lead, zinc, iron and copper by the Iberians and the Phoenicians, but it was as part of the Roman Empire that this became a major industry.

At around the time of the birth of Christ the Greek writer Strabo reported that there were 40,000 people (mainly slaves, it has to be assumed) working in the mines of Sierra Minera, and this source of prosperity brought more people to the area. The metals extracted were exported all over the Empire, but the Romans left open-cast mines which allowed remaining minerals and metals to be washed down by rainwater towards the Mediterranean to the south and the Mar Menor to the north.

These substances included heavy metals such as arsenic, lead, cadmium, manganese, zinc and others, and when more open-cast mining was undertaken in 1957 it was on a scale which dwarfed the operations of the Romans: in just 30 years 360 million tons of rocks were shifted.

While the dramatic infill of the bay of Portmán – a natural harbour used by the Romans 2,000 years ago before it became a dumping ground for sterile substances in the 20th century – has long been a cause for concern, the situation on the northern face of the mountains has grabbed less of the limelight. The mining stopped in 1990 and since then no more steriles have accumulated in Portmán – although a scheme to partly recover the bay has frustratingly stalled – but the ”rambla” runoff channels on the north-facing slopes of the Sierra Minera continue to carry harmful substances downhill to the Campo de Cartagena and then into the Mar Menor even today.

Thus, the Rambla de Las Matildes reaches Los Urrutias on the shore of the Mar Menor, the Rambla del Beal reaches Lo Poyo, the Rambla de Ponce carries water to Los Nietos and the Rambla de La Carrasquilla leads to Islas Menores.

The results will surprise many people: as the rate of sedimentation has accelerated in the Mar from about 4 centimetres per century in the past to 30 cm during the 20th century, the amount of metal and steriles in the lagoon has risen by so much that the Mar Menor is considered by at least one geologist to be an area of mining interest in its own right!

- THE DEVELOPMENT OF LA MANGA AND THE DREDGING OF THE GOLA DEL ESTACIO

Already during the 19th century the area along the inland shore of the lagoon had become far more built-up: not only did the fishing and farming communities in towns like San Pedro del Pinatar, Los Alcázares and San Javier become more prosperous, they also became favoured destinations for the population of the city of Murcia, now benefitting from annual summer holidays, to spend the warmest part of the year.

But in the mid-20th century the government of General Franco, keen to fuel the international tourism boom which had opened up the Costa Blanca, the Costa Brava and the Costa del Sol to floods of sunseekers from northern Europe, identified La Manga del Mar Menor as another possible area for expansion. An enterprising lawyer and empresario named Tomás Maestre Aznar acquired much of the land on the strip and high-rise construction soon made La Manga clearly visible from the mountains to the west of Cartagena and the Sierra de Carrascoy, just south of the city of Murcia. La Manga became one of the places to be seen for Spanish high society in the 1970s, with the grand scheme including the creation of a marina in the Mar Menor to rival that of Puerto Banús in Marbella.

But there was a problem. The golas connecting the Mar Menor with the Mediterranean were too narrow and shallow to accommodate any but the smallest boats, and thus in 1972 and 1973 Tomás Maestre was allowed to dredge one of them, the Canal del Estacio, to create a navigable waterway. As a result, La Manga had its marina, the Puerto Deportivo Tomás Maestre, the construction boom of tourist accommodation continued, the prestige of the area grew – due in no small part to the foundation of La Manga Club in 1972 – and Spain had a new tourist Costa, the Costa Cálida.

At the same time, though, the dredging of the Gola del Estacio also had other, less positive effects. Suddenly the rate at which water flowed between the seas on either side increased dramatically, and as a result the differential in temperature and salinity was substantially reduced. To say that the effects were noticed from one day to the next would be to stretch a point, but in comparison to the timescale over which the unique ecosystem of the lagoon developed it was radically altered in the blink of an eye.

Visitors of a certain age can remember ending long days on the beach in the Mar Menor caked in a crisp layer of salt, but within a couple of years the average salinity in the lagoon had dropped from approximately 55 to 45 PSU. In other words, the lagoon was now only 20 per cent more saline than the Mediterranean (as opposed to 45 per cent before the dredging), and the first signs of “Mediterraneanization” began to appear.

So too, unfortunately, did species of marine flora and fauna which had hitherto not prospered in the Mar Menor, including kinds of jellyfish, mussel, sea slugs and crustaceans which had not previously been able to survive here. Not only did they now prosper, but in doing so of course they provided competition for the “native” species in the Mar Menor where they had not had any before: the consequences, in many cases, were sadly predictable, and fishermen soon drew attention to the changes which were occurring.

In 1980, responding to pressure from the fishermen’s guild of San Pedro del Pinatar, a promise was made by Tomás Maestre to the Ministry of Public Works and Urban Development in the national government that he would restore the Gola del Estacio to its original dimension. This, of course, never happened.

- THE TAJO-SEGURA WATER SUPPLY CANAL

Much of the history of the Region of Murcia has been determined by the fact that while the soil in this part of south-eastern Spain is extremely fertile and the number of sunshine hours perfect for the cultivation of fruit and vegetable crops, the amount of water available has always limited and defined agricultural activity.

Until, that is, the early 20th century, when engineers were able to design and build the large dams which went a long way towards ensuring that the majority of the rain which falls on higher ground is eventually collected. These infrastructures provided a further boost to agriculture in Murcia and the rest of the Segura basin, enabling the sector to continue growing far beyond the capacity of previous centuries, and under the dictatorship of General Franco (1939-75) construction began on what eventually became the most important water infrastructure in Spain.

Engineer Manuel Lorenzo Pardo had reported to his superiors in Madrid after visiting Murcia in 1933 such was the potential of the Region that if necessary water from the Nile would have to be brought to the Region! However, after the interruptions brought about by the Civil War it was not until 1965 that the decision was taken to opt for a rather less ambitious solution, namely the construction of a massive infrastructure which would allow water from the headwaters of the River Tajo (or Tagus) in eastern central Spain to be transferred to the Talave reservoir in the province of Albacete and from there to the Segura basin, which contains not only the vast majority of Murcia but also parts of the provinces of Albacete, Alicante, Almería, Jaén and Granada.

From a civil engineering point of view the scale of the task remains impressive even today. The main canal runs a distance of 292 kilometres from Bolarque, between the reservoirs of Entrepèñas and Buendía, to the Talave reservoir, initially being pumped 245 metres upwards in a length of just over a kilometre at a rate of 33 cubic metres per second.

From the Talave the water can then be distributed all over the Segura basin through a network of secondary canals (or “sub-trasvases”).

The Tajo-Segura water supply canal finally came into operation in 1979, making it possible to plant crops which required irrigation in many more areas of the Segura basin and Murcia, and in consequence a period of rapid growth ensued in the agricultural sector. More water meant more agriculture and more demand for water, and this demand spiralled upwards as more and more crops were planted.

In economic terms, the effect on the Campo de Cartagena was dramatic, and towns from Torre Pacheco to Fuente Álamo were transformed by the sudden injection of profitability into the countryside. Coastal towns such as Los Alcázares and of course parts of Cartagena itself also benefitted, and with tourism still leading to further construction there was an unprecedented boom in the area.

But the effects on the Mar Menor were no less dramatic, although they took longer to become apparent. Whereas in the past the crops grown in the Campo de Cartagena had been mainly non-irrigation ones such almonds and carobs, the trees were now ripped out of the ground to be replaced with large-scale fields full of leaf vegetables, melons, peppers and other products, altering the natural landscape in such a way as to remove any natural barriers to surface water as it made its way towards the lagoon. In consequence, with contour ploughing abandoned in order to prevent stagnant water from lying in the fields and natural floodwater channels often obliterated by the need to create more farmland, the lagoon received more and more nitrates, pesticides and fertilizers every time significant rainfall fell.

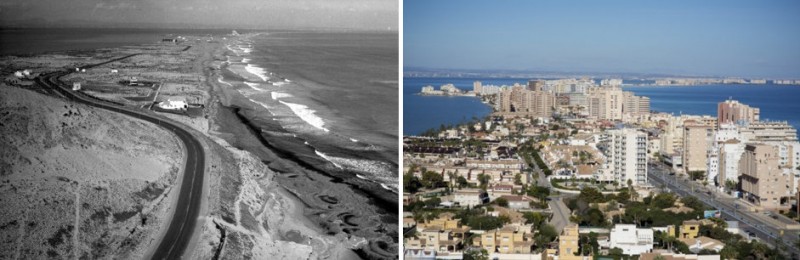

The image shows land next to the motorway in 1956 and 2013: contours and terraces disappear as dry crops are replaced by irrigation crops

The problems were exacerbated by the fact that the transformation of the Campo de Cartagena took place in the expectation that the capacity of the Tajo-Segura supply canal would be used to the full, but this has not been the case. The availability of water depends, of course, on the amount available in the headwaters of the Tajo, and it is always necessary to ensure that there is enough to maintain an ecologically viable flow rate in the longest river in the Iberian Peninsula.

The maximum annual transfer of water for irrigation established by the law is 400 hm3, of which 260 hm3 can be assigned to Murcia (and 122 hm3 to the Campo de Cartagena), but that maximum has never been reached. Figures published by the Condeferación Hidrográfica del Segura (CHS) show that between 1980 and 2018 the average annual total was 175 hm3, and during periods of long drought – ever more frequent as the climate crisis has gradually taken hold - the amount has been far lower. In the last five years the transfer has amounted to less than a quarter of that anticipated when the canal opened in 1979.

Despite this, though, it can still be asserted that a lot of the fresh water which ends up in the Mar Menor is actually collected in central Spain, completing a long journey south before making its way into the sea.

But faced with a shortfall in the water transfers from the Tajo, how did agriculture continue to thrive in the Campo de Cartagena if the anticipated water was not arriving?

The answer has for a long time been an “open secret”: by drilling.

- THE AQUIFER UNDER THE CAMPO DE CARTAGENA

Underneath the flat plain is a vast aquifer, which has been tapped into over the last 40 years by a huge number of barely concealed wells and pipes, with the brackish water extracted then being treated in mini-desalination plants before being used to water crops. According to some estimates, whereas water from under the ground provided around 30 per cent of all irrigation prior to the opening of the Tajo-Segura, as demand grew and supply dwindled it has at times contributed as much as 80 per cent.

Of course, there are by-products created by the desalination units employed by farmers in the shape of excess water, and this, inevitably is allowed to run off into the natural “ramblas” or floodwater channels which lead to the Mar Menor.

Land in the surrounding Campo de Cartagena naturally slopes down towards the coast, so the natural waterways cut by running water lead to the coast, many of them disgorging into the Mediterranean and some into the Mar Menor, water running thorughout the year as the soil filters the irrigation waters.

The result of all this is that not even the CHS water administration authority knows how much land is devoted to irrigation farming in the Campo de Cartagena, but one national government estimate points to a figure of around 60,000 hectares, of which 20,000 are illegal. At the same time, it has been found that 90 per cent of livestock farming concerns are in breach of water usage regulations in the area, mainly concerning leakages from approximately 500 manure storage pools, and from here harmful substances either filter down into the aquifer or run off into the lagoon.

It is believed that there is at least one borehole per square kilometre in the Campo de Cartagena (although again nobody, including the CHS, knows the number with any certainty and even the CHS estimate is incredibly vague at “between 1,000 and 2,000”), each of them requiring the treatment of the water extracted before it can be used in irrigation, and much of the treatment equipment is hidden underground by farmers aware that their activity is illegal. This unusable water either seeps back down into the aquifer or runs off into the Mar Menor, and although over the last couple of years the authorities have become a little more insistent in their attempts to clamp down on this activity the feeling is that may be too little, too late. Some studies report that there are now 300,000 tons of nitrates stored in the aquifer, waiting to find their way eventually into the Mar Menor.

In fact, the aquifer of the Campo de Cartagena is formed by a series of cavities containing water, on top of the other, which were formed during different geological processes. The lower layers have been over-exploited due to farmers drilling ever deeper in their search for water, but in the upper layer the problem is of a very different nature: constantly filled by water from the Mar Menor itself and by irrigation water filtering down to it, the water table is so high that at times water simply emerges out onto the ground.

This is a situation frequently referred to by the regional government of Murcia, which constantly demands that the national government and the CHS take action to lower the water table in the aquifer: this potential partial solution refers only to the higher layer which is full of seawater and irrigation water containing nitrates and fertilizers, and this inevitably eventually mixes with the water in the lagoon.

The water from the aquifer is not suitable for irrigation unless it is either mixed with less brackish water or treated - effectively, desalinated. But in 1994, after what was then one of the hottest and driest summers on record in Murcia, the CHS made a decision which in the light of what has happened since now seems incredible: with no clean water reaching Murcia via the Tajo-Segura canal it authorized the extraction of water from the aquifer, knowing that any farmer who took advantage would necessarily be treating it with clandestine desalination equipment.

The situation was partially regularized by the issuing of “temporary” 5-year permits to use such equipment, but with each machine costing up to half a million euros few farmers will have been keen to stop reaping the benefits: unfortunately there is a growing body of evidence which suggests that the CHS were fully aware of the situation but did nothing about it.

In short, the aquifer has been over-exploited for many years and this has added to the detrimental effects of intensive agriculture on the Mar Menor, where a study carried out by the University of Murcia concludes that irrigation farming is responsible for 85 per cent of the eutrophication of the lagoon.

(Note: eutrophication is a process which occurs when a body of water becomes excessively enriched with minerals and nutrients which induce the rapid proliferation of algae. It is sometimes associated with oxygen depletion of the water and often brings about an "algal bloom" (a significant increase of phytoplankton) which turns the water green. Fertilizers are recognized as a common cause of eutrophication.)

- THE MAR MENOR PROTECTION LAW OF 1987

One of the saddest aspects of the deterioration of the Mar Menor is that in fact legislation to protect the lagoon was passed over 30 years ago but was later scrapped by subsequent governments.

In 1987 the PSOE regional government in Murcia introduced what was considered to be a pioneering piece of environmental legislation designed to leave the Mar Menor completely free of polluting substances within 5 years. The Ley de Protección del Mar Menor was published by the Official State Bulletin on 16th July 1987, having been drawn up by the regional minister for Public Works, José Salvador Fuentes Zorita, who later became head of the CHS, and passed during the presidency of Carlos Collado Mena.

Among the stated aims were to reduce the runoff of harmful substances from agricultural and mining concerns in the Campo de Cartagena and the mountains of Sierra Minera.

However, due to the restrictions it placed on land use in the Campo de Cartagena it met with strong opposition from property developers, who were supported by Federico Trillo, a PP member of parliament and a native of Cartagena who later became Minister of the Defence. Sr Trillo and over 50 other PPs protested over the legislation in the Constitutional Court in an attempt to have it repealed, but, after no less than 7 years of deliberations, their objections were systematically overruled one by one and the law remained in force, in theory at least.

This changed abruptly after the regional elections in 1995: when Ramón Luis Valcárcel of the PP became president of the Murcia government (a post he would hold until 2014), opposition to the legislation strengthened, and finally, in 2001, it was summarily replaced by the Regional Land Law with a one-sentence explanation: “the socialist law harmed the interests of urban development in the area and made it possible to suspend municipal building licences”.

With that sentence the law to protect the Mar Menor was dead and buried, but looking back now it can be seen as an almost visionary piece of legislation. Many of the measures contained in the “zero runoff” proposals outlined by the Ministry of Ecological Transition in 2019 were almost carbon copies of those put forward in 1987, but, like so many visionary projects, it seems it was too far ahead of its time.

The law identified the need for protection in and around the Mar Menor as a result of the “transformation of socio-economic structures and the model of development” of the preceding decades, referring to the boom in tourism and the massive increase in irrigated crop farming following the opening of the Tajo-Segura water supply canal in 1979. Reference was also made to the “impact and deterioration” suffered by the environment to justify an adjustment to land use laws.

At the same time special status was to be granted to the ecosystems of the lagoon and the surrounding land areas according to their ecological, scientific, cultural, recreational and socio-economic characteristics, while urban planning was to be compatible with environmental protection – this was the aspect which allowed the regional government to overrule Town Halls in the granting of building licences.

Similarly, systematic controls were to be put in place on runoff water from all sources, including crop farming, livestock farming and mining, and the traditional bathing jetties along the shore of the Mar Menor were to be protected.

All of this will ring a series of bells very loudly indeed among readers acquainted with the principal measures which are being proposed and endlessly discussed, but not yet implemented, over three decades later.

Once the Ley de Protección del Mar Menor had been removed (and it is alleged that it was never strictly implemented while still in force), there were far fewer legal limits on urban development and farming. A Greenpeace report indicates that between 1987 and 2011 the amount of built-up land on the coast of the lagoon increased by 55 per cent, while other sources including the World Wildlife Fund and ANSE assert that around a quarter of all irrigated crop farming in the Campo de Cartagena is on land where this activity is theoretically not permitted by the CHS.

- EXCESSIVE URBAN DEVELOPMENT

The level of urban development in La Manga and along the inland coast of the Mar Menor has been, in a word, staggering. Photographs from the early 20th century show that only very occasional huts and agricultural storage buildings existed in La Manga, while the increase in the amount of concrete and tarmac in the Campo de Cartagena has transformed the landscape only marginally less dramatically.

In 1956 only 7 per cent of the land within 100 metres of the Mar Menor was built-up, amounting to 138 hectares, but by 2010 the figure had risen to 40 per cent, or 756 hectares. Apart from La Manga the town which has grown most in size is Los Alcázares, and it is perhaps no coincidence that this is also the one most vulnerable to flooding in episodes of heavy rain such as those which saw the streets of the town under water and mud three times in only four months in late 2019 and January 2020.

Neither has the construction boom been limited to the front line. In the area around the Mar Menor the total built-up area increased by 6,000 hectares between 1986 and 2016, with the lie of the land being altered and tarmac replacing soil to such a large extent that inevitably the capacity of the land to absorb water has shrunk.

The results include not only more flooding but also more nitrates being washed into the lagoon by the excess of surface water, and although moratoria have been issued concerning new construction in the area the opinion of the naturalists’ association ANSE is that, at least until now, there have been so many exceptions to the bans on building that the legislation has been practically meaningless.

- URBAN WASTE

As towns around the Mar Menor and in the Campo de Cartagena grew, so too, of course, did their population and the amount of sewage and other urban waste they generate. Until relatively recently a percentage of that waste was dumped into the sea, and even when water treatment and purification plants were built the by-products of the purification process had to be disposed of somewhere.

While the treated water was put to good use (including irrigation farming, of course) these by-products were released into the “ramblas”, and ANSE have been protesting at the practice for at least 20 years. Astonishingly, it was not until the 1980s that the sewage network was even completed along the shore of the Mar Menor, and only in 1992 were 33 million euros set aside for the construction of purification and treatment plants.

Nowadays the infrastructures are in place and operational but defects and leakages in the sewage and treatment pipes are frequent, especially during times of heavy rain and when the population swells during the summer, and in consequence sewage and untreated water can still make their way into the lagoon: one University of Murcia study concludes that as much as 15 per cent of the problems in the Mar Menor can be attributed to urban waste.

- THE LOSS OF WETLANDS

It is important to remember that the ecosystem of the Mar Menor does not consist only of the lagoon itself but also of the land around it, which includes various wetlands. These wetlands act as a natural barrier protecting the Mar Menor from runoff and floodwater, since the water accumulates there, and also as a storage tank in which water can begin to be “cleaned” by the natural actions of plants on the potentially damaging substances contained in that water.

But since the start of the 20th century over 50 hectares of wetlands around the Mar Menor have disappeared due to a variety of factors: the suspension of production in the salt flats of Marchamalo, urban development around the wetlands of Lo Poyo, the marina of El Carmolí and the urban development which has led to the shrinking of the wetland areas in La Manga, to name but a few. In consequence, as the Mar Menor has come under every greater attack its defences have been denuded and abandoned.

- MANMADE ALTERATIONS TO THE COASTLINE

With the growth of tourism and water sports activity the need to generate revenue has seen a progressive alteration of the shoreline of the Mar Menor, with the construction of ports, marinas, jetties, piers, breakwaters and other structures and the “regeneration” of beaches as local and regional authorities do their best to ensure that “sand” is not missing from the typical “sea and sunshine” offer in the Costa Cálida.

In essence, rather than a happy geographical accident, for some people the Mar Menor has become little more than a giant saltwater swimming pool and boating lake. The ten marinas in the lagoon boast 3,853 mooring points (and despite legislation outlawing the practice plenty of owners still hitch ropes to submerged concrete blocks elsewhere in the lagoon). The number of ports per kilometre in the Mar Menor is almost five times higher than in Barcelona, and all of this coastal development alters the natural flow patterns (and therefore the distribution of sediment) in the shallow water.

At the same time, of course, motor boats contribute to the presence of unwanted substances in the lagoon, while the “regeneration” of beaches (artificially added sand) eventually leads, as has been pointed out by naturalists for the last 30 years, to the creation of more sediment: hence the scientifically justified nostalgia for the bathing jetties which were a feature of the Mar Menor in the early years of the last century, before they were replaced by wide beaches.

To put this into perspective it is worth pointing out that as recently as the 19th century the Mar Menor barely had any sandy beaches: one of the few places where the natural state of the shoreline can still be seen is at La Hita, between Los Alcázares and the aerodrome of San Javier, and this is now considered a “wild” stretch of coastline where reed fields make access to the water difficult and inconvenient.

- THE CLIMATE EMERGENCY

As if local developments around the Mar Menor were not enough to threaten the ecosystem of the lagoon, it is now almost universally accepted that the Earth’s climate is changing with potentially disastrous consequences.

From the point of view of the Mar Menor, the warming of the climate has hastened the deterioration of the marine environment. One of the changes which is already being seen is that extreme weather events such as torrential storms are becoming more and more common: as the atmosphere of the planet warms its capacity to retain water vapour is increasing, and for this reason there is more moisture released when the conditions are right for rain.

In this context the “gota fría” storm of September 2019, reckoned by meteorologists to have been the most extreme for at least 50 years, should probably not be considered a once in a lifetime event, and the subsequent violent and destructive storms in December 2019 and January 2020 serve only to illustrate the point further.

And every time there is heavy rain in the Campo de Cartagena, of course, there is floodwater heading for the Mar Menor…

Much of the water, debris, silt and agricultural produce which poured into the Mar Menor in September 2019 came from Torre Pacheco and the municipalities surrounding the Mar Menor, many kilometres from the lagoon, flowing downhill to the coast. The average rainfall in the whole of Murcia between 11th and 15th September 2019 reached 149 millimetres: in La Manga the total reached 335 millimetres, with other notable figures including 294.6 mm in Los Valientes (Molina), 264 mm in Torre Pacheco, 241.9 mm in Cieza and 239.4 mm in Alcantarilla.

But in the longer term, the climate emergency might just put the Mar Menor out of its misery.

As polar ice melts it is forecast by some analysts that the sea level will rise by 1.5 metres before the year 2020. If that happens, the flow of water between the lagoon and the Mediterranean is likely to increase to the point where any difference in water quality between the two seas is minimal: in other words, the unique marine environment of the Mar Menor will simply no longer exist.

APPROACHES TO SOLVING THE PROBLEMS

This list of 11 factors to take into account when attempting to draw up a strategy to save and protect the Mar Menor is far from definitive. But it does illustrate the complexity of the situation and the fact that no one measure will solve the problem: to stand a chance of success any approach will have to be multi-pronged, multi-disciplined, strictly enforced and maintained for a long time, with the economic interests of various sectors being relegated to secondary importance in deference to the marine environment of the lagoon.

Many scientific studies have been undertaken since the eutrophication of the lagoon in 2016, many plans proposed, debated, examined and rejected, many political discussions undertaken and many, many, many words written about the topic, but the situation today remains as complicated as the history of why the problems currently affecting the Mar Menor exist.

There is no short-term solution. There is no simple measure that will solve the problem. There is no single body, individual or group which is entirely to blame for the current situation. And there is no simple way to predict the evolution of the current problems in the immediate and long-term future.

Last year the water quality improved considerably as the lagoon recovered from the effects of the 2016 "green soup" and the efforts undertaken by the authorities to limit water run-off and find solutions to the problems, work undone by the last two episodes of torrential rains.

By Easter the beaches will once again be ready to receive the annual influx of summer tourists, their sand replaced, promenades cleaned and rebuilt, water visibility is likely to improve as silt and debris is removed or settles, algal growth cleared and the marine environment begins its own natural processes of recovery, businesses praying that the many thousands of city dwellers who own the holiday apartments fringing the lagoon will spend their money as normal for the summer season.

And that there are no more storms before the summer season.

But what is the long-term future for the Mar Menor?

Unfortunately, that's a question it's currently impossible to answer.

Join the Mar Menor group on Facebook for info about Los Alcázares, San Javier, San Pedro del Pinatar, Torre Pacheco, La Unión and Cartagena and keep up to date with all the latest news and events in the Mar Menor: https://www.facebook.com/groups/MarMenorNewsAndEvents/